Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review

Europe:

July 14th: After an unsuccessful attempt in 1865, the Great Eastern at least completes its mission at connecting Europe and North America via telegraph wire. The wire comes to rest in Newfoundland, and one of the first messages is a greeting from Queen Victoria to the Viscount Monck saying “We wish well our subjects on this historic day,” in a message proudly hailed as making Canada a “trans-Atlantic nation” by commentators. In September, the lost cable of 1865 will be dredged up, repaired, and connected to North America to create two working cables.

July 30th: Sweden-Norway and Denmark meet to discuss a mutual defence treaty. In the aftermath of the Treaty of London, both nations feel threatened by potential encroachment by Prussia into the Baltic. A feeling of brotherhood between all the Scandinavian countries runs high and the “tripart” flag combining the flags of Sweden-Norway and Denmark is flown by crowds in both Stockholm and Copenhagen by enthusiastic crowds, in Stockholm as a sign of solidarity with Sweden and in Denmark as a sign of disapproval of the current government. The Treaty of Stockholm will affirm a defensive pact between the two nations, paving the way for further cooperation in the coming years.

“The exact motivations of Dmitry Karakozov were easily found. The murderer of Tsar Alexander II had a manifesto in his pockets, and the shot that killed the emperor in the Summer Garden had alerted the guards. The assassin had hardly attempted to flee, being easily detained. The day after the assassination a letter was delivered to the Governor of St. Petersburg wherein he stated “I have decided to destroy the evil Tsar, and to die for my beloved people[1],” and he would soon be given his wish. Moved to the Peter and Paul Fortress, he was interrogated and sentenced to death in September of that year alongside a number of other alleged conspirators.

In the face of his father’s reform minded government in this brief reign, the young Tsesareveich would find his view of the world transformed. His father’s emancipation of the serfs had been radical, his efforts to reform self government and rationalize the laws on the French model admirable, and was seen as a step towards the liberal ambitions of Europe. Though he had respected his father’s goals and wishes, seeing him killed in the streets of St. Petersburg planted the all important seeds of doubt in young Nicholas’s mind. At such a young age he was impressionable, and one of the youngest tsars to take the throne yet. He determined that he would outlast his fathers bare 10 year reign. But for that, he might have to become a man of iron…” - The Iron Tsar: Nicholas II, Ian Branagh, Oxford, 1995

“...the Austro-Prussian War, occasionally known as the Ten Weeks War or the Brother’s War, was the second of the accepted Four Wars of German Unification, the 1848 nationalist sentiment underscored the first attempt and underlying urge for German unity among intellectuals. The breaking point which would divide the German speaking peoples for another generation was a broad cultural divide between the Prussian and Protestant dominated north, and the divide between the Austrian and Catholic dominated southern states who disagreed on general politics and matters of governance. That the Prussian state sought to rectify this by force was, at the time, seen as folly by immediate post-war writers who criticized the Machiavellian machinations of Bismarck which helped to only drive a wedge between the German speaking peoples.

Indeed the precipitating crisis can be placed squarely on Bismarck’s shoulders. The Prussian Chancellor had been severely displeased with the final treaty ending the Second Schleswig War, seeing it as an avoidable capitulation by a feckless Austrian ally. The annexation of Holstein and much of Schleswig into the German Confederation was less of a prize than he hoped. To that end, he worked tirelessly to frustrate the work to put an Austrian friendly prince on the throne. First maneuvering to block the accession of Frederick VIII, the Duke of Augustenberg to what all the other German states considered his rightful throne, and finally, by threatening the annexation of the whole Duchy if he did not get his way by preventing Austrian officials from calling the diet of the Duchy. This incensed many of the smaller German monarchs who looked to Austria to right this wrong.

Efforts to avert war in the German Diet came to naught, and Bismarck would simply walk out, with an alliance of smaller states supporting Prussia, but the majority of German kingdoms siding with Austria…

…simply put Moltke’s planning had resulted in a masterstroke. The Prussian forces had routed the forces of the lesser kingdoms and driven them across the Main, driving into Austria and pairing away many of the smaller German states forces. The Saxons had been driven into the Austrian arms, and the maneuvering against the Federal VIII Corps in the Southern German states seemed poised to deliver another victory to Prussian arms. As the two armies maneuvered towards the village of Königgrätz it seemed as though the decisive blow would be struck.

Instead, the Battle of Königgrätz has gone down as one of the single most catastrophic days in Prussian military history. Moltke’s meticulous organization meant that the battle opened more or less in his favor…

…the tenacious Austrian defence of the Swiepwald made it so that Moltke’s timetable was frustrated by surprisingly effective Austrian artillery. As a result, the Prussian advance stalled, forcing more forces to be detached from the attacks towards the Austrian center. King Wilhelm, alongside his entourage including Bismarck and Moltke, rode to where his reserves from First Army were maneuvering and prepared to issue the order to support the attack. That was when a nameless imperial artilleryman launched the shell that most likely changed the course of German history.

There was no possible way the shell could have been deliberately aimed, the range was simply too improbable. Likely it was another arcing shot aimed high to frustrate the Prussian advance. Instead, it landed directly on top of Wilhelm’s entourage. Bismarck and the king were killed instantly, Moltke would survive his wounds long enough to order a withdrawal to a defensive position, but expired shortly thereafter, with von Roon being carried from the field and surviving. However, at the most inopportune moment, the Prussian state had been effectively decapitated.

Confusion reigned in the Prussian ranks and the advance slowly, surprisingly, stalled. Rumors circulated in the ranks, but officers attempted to quell them. The fighting spirit of men, now confused why their so far successful attacks had stopped, began to droop as men watched officers briefly lament the death of their king.

The arriving Prussian Second Army under the command of the Crown Prince, merely added to the considerable confusion as Benedek, sensing hesitation in the Austrian ranks, ordered the 8th Corps and the Reserve Heavy Cavalry division under General Carl von Egbell to move and assault the flank of the Prussian forces, but instead caught them forming in marching order. The ability of Prince Friedrich to organize his forces was hampered by both the news of his father’s death and the urging of his officers and courtiers that he must quit the field. Instead, Friedrich sought to salvage a suddenly savage situation by ordering a defensive formation and getting his battered army into shape…

…The concurrent Third Italian War of Independence had gone just as poorly. The stinging defeats in Venetia and on the seas at Lissa where the Italian Navy, in spite of a small superiority in ironclads[2] had been soundly defeated, meant that the Austrians were in high morale as the war went into August…

Though the subsequent, hesitant, offensive by the Austrian forces through the Ore Mountain Passes had resulted in stalemate, there was the sense that the war could continue on another front. The Prussian defeat at the Battle of Tauberbischofsheim, though minor, resulted in a renewed sense of urgency to fight by the smaller southern kingdoms. Crown Prince Friedrich, shorn of a large advising body and with a small political crisis on his hands, instead offered negotiations rather than engage in a protracted struggle…

…mediated by a distracted Russia, the Treaty of Krakow would impose few sanctions on either party. The Austrians pointedly excluded the Italians who signed a separate peace, renouncing their claims to Venetia in the Treaty of Vienna. The Austrians renounced their influence over the Northern German states, and grudgingly accepted the formation of the North German Confederation, which they saw as a “Greater Prussia” in all but name. Prussia meanwhile, would not force the issue of the Southern German states, and acknowledged the independence of the Kingdom of Saxony, which the Austrians insisted on as a point of honor. The Northern German Diet was established, with the Southern German Diet declared as a new body which represented these smaller states.

This would effectively split the German peoples into two halves. In the north, Prussia ruled in all but name as the most powerful single German state amongst a majority Protestant people. In the south, Austria was supreme, but had her now loyal allies in the smaller, primarily Catholic states who looked to Vienna for guidance and protection from what these states now saw as effective Prussian domination and absorption as they watched the rulers of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, Nassau and Holstein overthrown. These regional faults were the precursor to all future conflicts as the peoples there saw the hamfisted attempts by Prussia to coerce them into their sphere by force as just as, if not more, threatening than latent anti-French feeling. Austria, though she had not covered herself in glory, could walk away with pride at having not lost any territory or honor. Prussia had satisfied some, but not all, of her strategic goals, but alienated the Southern states in doing so.

Krakow was called a ‘peace which solved nothing and satisfied no one’ which in the measure of time could be called correct. It did not end the German Question to anyone’s satisfaction, and instilled a measure of hostility between north and south. Ultimately, it would bring bloodshed to Europe again…” - The Austro-Prussian War, Thomas Jones, Oxford University, 2001

November 9th: After a revolt against Ottoman rule began on Crete, the intervention of Isma’il Pasha and Egyptian troops restores order over much of the island. The most ferocious fighting takes place at the Arkadi Monastery where the last organized insurgents have fled. The final battle is a bloody hand to hand conflict in which 800 of 900 insurgents, including women and children, are killed in the close confines. The battle further sours liberal opinion in Europe against the Ottoman Empire.

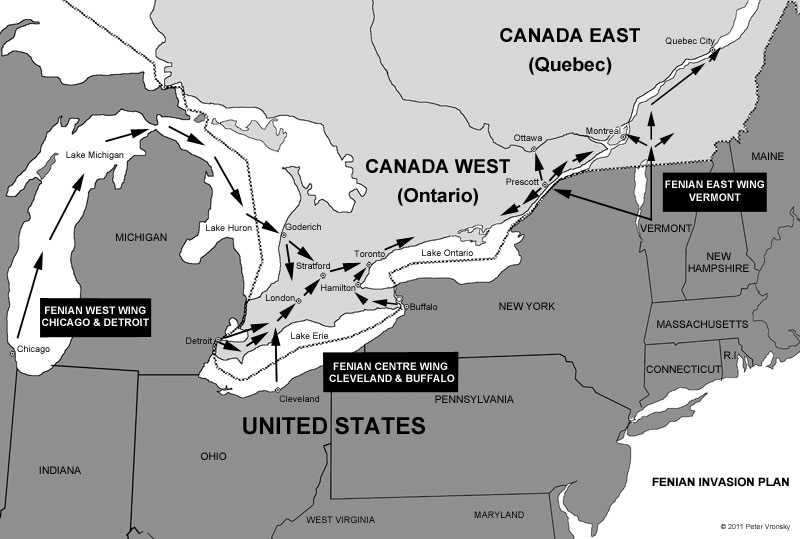

November 18th: A group of Fenian conspirators meet discussing the ship St. Patrick, a former Union commerce raider purchased by Fenian agents, to smuggle arms to Ireland. The move is financed by the Fenian Brotherhood who are amassing arms for a rising in the coming year. Unbeknownst to them, the meeting has been infiltrated by British agents, who duly pass the information on to Dublin Castle.

Asia:

“The exact details of the deals made between the surviving Mandarin’s under the authority of Yicong[3] and Mikhail Chernyayev and his Cossacks is the subject of considerable scrutiny in both Russian and Chinese scholarship. Sources from Russia claim that the Manchu had been taken under the protection of the tsar in exchange for all the territory on the banks of the Nen River and into the east bank of the Liao River, namely Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces, but also tracts of Inner Mongolia. Whether that was intentional or not is unknown, as Chernayayev[4] may have been operating well outside the scope of any orders of the acting regional governor Nikolay Busse. The Manchu would later claim they only offered parts of Inner Mongolia and lands east of the Nen. However, the Russians interpreted this as authority up to the Liaodong Peninsula, which they greedily annexed, landing a force of 2,000 sailors and soldiers in late 1866 at Port Arthur against a bewildered local garrison who had been under orders not to engage foreigners. Cossack troops would then pour into the other territories, augmenting what few Manchu forces remained as a bulkwark against further expansion.

The news belatedly reached Nanjing in November of 1866, and it presented the new dynasty with a complication. The Emperor did not believe China was yet organized enough in the wake of the fall of the Qing to take on the foreigners, and it was mistakenly assumed that action against one would invite the intervention of other powers, the various competing ambitions between the western powers being mostly unknown to the Armies of the Proclamation and their leaders. Furthermore, forces had already been sent chasing Mongol forces loyal to the former Qing, combating rebel troops across Central China, and to fight the ongoing revolt on the northwest frontier[5]. Mustering a large force to evict the Russians would be doable, but a major distraction from solidifying control over the remainder of the empire.

Grudgingly, the court would accept the Russian offer of recognition of their dynasty in exchange for the annexation of these provinces, and a new border in Manchuria. However, the court in Nanjing would deny ever offering tributary rights to Korea, while the Manchu would do the same, despite the Russian officials claiming both sides offered the tsar status over the kingdom. It was a thorny issue which would long vex the region. It was most likely a naked attempt to control the peninsula, but one which was, unlike the seizure of Port Arthur and slow absorption of the three northern provinces, beyond the immediate Russian means.

It was, however, further proof to the new dynasty that the empire had to reform, and above all, self-strengthen to resist such greedy efforts by the barbarians…” - Twilight of Dynasties: The 19th Century Crisis of China, Sylvester Platt, Oxford Publishing, 2012

October 11th: French forces launch expeditionary raids against Korea, intending to open the country to foreign trade, similar to successes against Japan or China. Despite a month of campaigning along the coast, and primarily against Ganghwa Island, the French squadron is unable to compel the Joseon Dynasty to open its ports. This is part of a broader conservative turn in politics under Yi Ha-ung, who wishes to maintain strong relations with China and isolate his country from Europe and other outside influences. This will include firing on foreign merchants and warships which enter Korean waters.

South America:

“After the defeat of Paraguayan forces at Tuyuti and Curuzú, the Paraguayan forces were in disarray, falling back all along the front. In these battles the Paraguayan army had lost some of its best troops and losing over 15,000 men, a quarter of the pre-war Paraguayan military. Lopez’s invasions of both Uruguay and Brazil had been defeated, leaving him on the defensive. He quickly realized that there was no way he could decisively defeat all the armies arrayed against him and instead opted to sue for peace. In order to do so he invited the leaders of Uruguay’s Colorado faction, Venancio Flores, and the leader of Argentina, President Bartomolé Mitre, to a conference to discuss peace at Yataytí Corá. Overtures to the Brazilian government were rejected as it had become imperial policy that the only way the war would end was with the overthrow of Lopez.

Immediately the talks broke down as Flores, both in solidarity for Brazil’s position and blaming Lopez for the start of the war, withdrew from the talks after a stormy discussion with the Paraguayan dictator. This left Mitre as the only allied representative who was willing to discuss peace. After 5 hours of discussion, mostly helmed by Lopez, the two men drew up a protocol where Lopez claimed he “wished to find a conciliatory peace for all parties” but Mitre left the talks knowing it was unlikely his allies would accept anything less than Lopez’s unconditional surrender. Having drawn this to Lopez attention, Lopez informed him that he would not relinquish power.

In response, the allied armies began to march into Paraguay proper in early September…

The allied forces, now some 20,000 strong, came upon the Paraguayan defences at Crurpayty. These were an impressive line of fortifications along the River Paraguay which had been dug and fortified as a redoubt against a river crossing and to help defend the Fortress of Humaitá, colloquially known as “The Gibraltar of South America” to those in the conflict. It was a serious obstacle to the allied advance, and it needed to be taken. Lopez established his field headquarters there and would watch the advancing allied fleet and army with a mixture of trepidation and contempt. True he had only 5,000 men left, but the fortress was strong and his defences well placed.

Even so, the allies were confident in their numbers and began a naval bombardment on the entrenchments facing them on September 22nd 1866. However, they stayed far upstream, away from the guns of Fortress Humaitá. Thus, despite the 5,000 shells fired, meant they had limited accuracy and inflicted little damage on the Paraguayan fortifications.

As the allied forces mustered to assault the trenches, matter became worse when it was assumed by the allied commanders that the defences had been silenced. Instead, they had been misled. Though the navy had indeed bombarded a series of trenches with great effect, this was not the actual Paraguayan defensive line, and the allis passed through them without encountering any resistance. This led the allied leaders to believe they would simply be rolling over the Paraguayans. Then they came upon the true trench line and calamity ensued.

General Diaz ordered his entire artillery section to open up a cannonade on the advancing attackers. Canister and shell fell on the assault columns which were maneuvering through muddy ground and inflicted enormous casualties…

…ordered a retreat by 2pm. In the end it was the most decisive victory by the Paraguayan forces in the war. In suffering only 92 casualties they inflicted 4,227 losses on the allied forces. The Battle of Curupayty would stall the allied advance on Paraguay for months, and resulted in serious political fallout in the camp of the Triple Alliance.” - War of the Triple Alliance, Diego Abente, 1987

September 1866: After the combined might of Bolivia, Peru and Chile all declare war on Spain in response to the provocations against the Chincha Islands, the ports of the Pacific Coast of South America are closed to Admiral Núñez’s fleet. Despite bitter and indecisive battles at Abatao and the bombardment of both Callao and Valparaiso, a battle in which both sides declare victory, Núñez is forced to withdraw his fleet to Spain, allowing the Peruvians to bloodlessly reoccupy the islands.

Both Peru and Chile believe they have fought off a Spanish attempt to reimpose its will on South America and reconquer its Pacific coast holdings in South America. To that end, they believe they must launch a pre-emptive strike on the Spanish possessions in the Philippines in order to disabuse the Spanish from ever setting foot in South America again. As Spain has refused efforts to reimpose a peace treaty, the Combined Fleet of Peru and Chile makes preparations for a strike against Manila under the command of Manuel Villar Olivera[6].

The Pacific:

July 5th: The Kingdom of Hawaii and the United States sign a free trade agreement pertaining to the sugar trade and tax and duties on American goods into Hawaii[7]. The sugar planters of Hawaii are given preferential treatment regarding their imports, while American goods imported to Hawaii will have no duties upon them, a preferential arrangement for all parties. It marks the nadir of Kamehameha IV’s relations with the United States.

“The final great military defeat of the King Movement came in the spring of 1866, when the Maori fortifications at Ōrākau were assaulted. Compared with the somewhat clumsy and cumbersome advances of a year prior, Cameron, well secure with his rear and supply lines established by land and sea, led 4,000 men inland. The Maori were compelled to withdraw from the ever mounting pressure and the skillful fire of British artillery, the battle playing out as such…

…by the end of the 4th of May the remainder of Maori forces, driven from their fortifications, withdrew deeper into the interior and the lands of the northern tribes. The use of indiscriminate fire by the British assault killed many of the Maori wounded, and left dozens trapped inside. Those who could flee chose to do so, but Cameron had angled to surround the whole of the great pa and in doing so, prevented all but some 400 from escaping. The pursuit was vicious, with those falling behind or the wounded unable to walk, simply killed out of hand by their British pursuers. The King decreed that his people would move into the lands beyond the Puniu River, with a well fortified line of pa stretching across the new territory. It was decreed that any European who crossed this line risked death.

This course suited Cameron just fine. He was wary of more assaults against Maori trenches and determined to launch a punitive campaign into the Tauranga where he felt supplies and gunpowder were being brought to the Kingites by sea. The policy of overwhelming firepower used against the Maori continued, and from 1866 to 1868 the war devolved largely into skirmishes and driving the Maori out of villages and establishing redoubts and secured means of communication, burning as they went. This set the stage for later settlement. The Colonial government meanwhile, was anxious to get on with land annexations. The Kingites were, mostly, forced to accept this state of affairs, with over 16,000km of land confiscated from the Maori by 1870…” – Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV

-----

1] In reality the letter never got delivered, but here I feel there’s some dramatic oomph to it arriving properly. This was one of those close calls for Tsar Alexander II, and only a jostling of the assassin’s elbow may have saved him.

2] The loss of the two ironclads to the Italian fleet at Lissa when the US took them for Sandy Hook isn’t decisive, but it is used as something of a copout by some Italian politicians and admirals as to why they lost. It has earned the United States a significant amount of ire from Florence, the Italian capital for now.

3] Prince Dun (or Yicong), a relatively minor Manchu noble who had been an ally of Cixi as his only defining factor. Here he barely escaped with his life from the Han armies and has extreme PTSD and a fear that the Han will come north and “finish the job” so sells this territory to the Russians under dubious authority that no one in Nanjing is in a position to fundamentally argue.

4] Based on his exceeding of orders he carried out when invading what became Uzbekistan in 1864-65 OTL, hence his being “kicked upstairs” to the East. A time of opportunity that he may or may not be rewarded for.

5] The Dungan Revolt was a long simmering revolution of mostly Hui Muslims in the Northwest who were fighting from 1862 to 1877. Let’s just say that the effective control that the new dynasty will have over this region is going to be iffy for a long time.

6] Historically former Confederate officer John Randolph Tucker was placed in charge, but thanks to the differences he’s currently pulling a nice job in the Confederate Navy, hence why Peru is leading the show here. That makes the a little bolder and more self assured.

7] This is only possible here because there’s no Southern sugar interests to lobby against it in Congress and there’s no desire to support them in the US.