Saphroneth

Banned

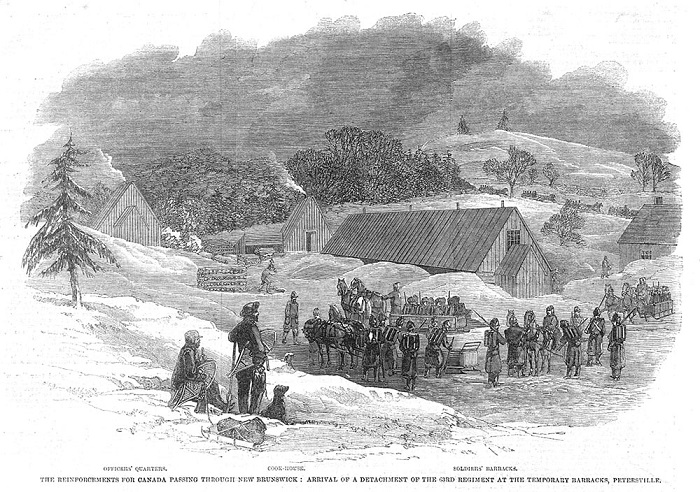

http://67thtigers.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/reinforcements-from-colonies-for.html

This seems like a useful addendum - hopefully this will help you put some names to the battalions, EC. I know it's a bit of a headache going from "eh, 80K troops" to specific battalion names.

Basically sums to 68-69 battalions of regulars.

I happen to think this could be increased a bit by deploying overseas-militia to take on some of the garrison duties, or just by using them as second-line replacements able to hold fortified positions while training up to Regular quality.

This seems like a useful addendum - hopefully this will help you put some names to the battalions, EC. I know it's a bit of a headache going from "eh, 80K troops" to specific battalion names.

Basically sums to 68-69 battalions of regulars.

I happen to think this could be increased a bit by deploying overseas-militia to take on some of the garrison duties, or just by using them as second-line replacements able to hold fortified positions while training up to Regular quality.