To be fair, the signs were there as soon as the Nazis took power, so I can't really blame them. And it's not far-fetched to prioritize Italy over Yugoslavia, especially since the latter doesn't look terribly stable. It will have the effect of shaking the rest of their allies in the East tho, and Romania might not feel so confident of French protection anymore. Czechoslovakia is another beast cause they don't really have another option.I really don't want to just dump on France like a lot of AU stories which focus more on Germany do, but wow, even without the benefit of hindsight, France in this era is really just basing its entirely personality on "fear of Germany" and doing horribly dumb things as a result of this blind paranoia. Yes, they won't be the same dumb things without Hitler, but a lot of them preceded Hitler and... wow.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

8mm to the Left: If Hitler Died in 1923

- Thread starter KaiserKatze

- Start date

Personally I feel that the Little Entente was a way stronger alliance than a Franco-Italian one would have been. Even without the benefit of hindsight, I think that relying so heavily on Great Powers is a mistake. I mean look at WW1, Serbia and Bulgaria punched so far above their weight while Austria-Hungary and Italy did not.To be fair, the signs were there as soon as the Nazis took power, so I can't really blame them. And it's not far-fetched to prioritize Italy over Yugoslavia, especially since the latter doesn't look terribly stable. It will have the effect of shaking the rest of their allies in the East tho, and Romania might not feel so confident of French protection anymore. Czechoslovakia is another beast cause they don't really have another option.

Also guess who has COVID wheeeee... well, at least it means some time to write and rest.

Feel better soon!Also guess who has COVID wheeeee... well, at least it means some time to write and rest.

Get better soon!Also guess who has COVID wheeeee... well, at least it means some time to write and rest.

While the Little Entente was more than enough to serve its primary objective, that is to contain Hungary, I think that several realistic constraints of the countries and the alliance itself prevented them from being a credible force in defending against the Great Powers that could threaten its members.Personally I feel that the Little Entente was a way stronger alliance than a Franco-Italian one would have been. Even without the benefit of hindsight, I think that relying so heavily on Great Powers is a mistake. I mean look at WW1, Serbia and Bulgaria punched so far above their weight while Austria-Hungary and Italy did not.

Firstly, lines of communication and very shit between the countries. While they are all theoretically contiguous, the main land borders are in the underdeveloped Carpathians region, with the additional complexity of it being a mountain range. As far as I know, there are no railways between the countries that do not pass through others. That bodes really badly for a response against anyone that isn't Hungary, where the problem would solve itself.

Now, even handwaving that and assuming troop deployments could go flawlessly, would the countries really send their armies away? With their limited size and populations, they only have so many soldiers, and all of them have some threat to their own borders they can't afford to ignore. Can Romania really send soldiers to Yugoslavia when the Soviets could just decide it's a great moment to stake their claim to Bessarabia? And that same logic works for any situation, given that Czechoslovakia has Germany and Yugoslavia has Italy.

On top of that, the limited industrial capacity of the countries should be considered. While Czechoslovakia is the exception to this with a quite robust industrial base, I don't know if that is enough to supply everything Yugoslavia and Romania would need. That means that dealings with Great Powers are still necessary.

So, all that considered, could Yugoslavia be sure that with the Little Entente alone they'd have adequate support if Italy decides they want Dalmatia? Could Romania, if the Soviets decide to demand Bessarabia? The answer is a quite resolute no. That means that, at least for defending against other Great Powers, the countries of the Little Entente will still have to find themselves someone to support them.

That's a good point, I had forgotten about the fact that all of them have that fear of an enemy at their back if they go to help one-another. Of course, it wasn't helped by France's post-WW1 decision to turn inwards and build its fortifications instead of helping them to interconnect with each other and build a bullwark against Germany.While the Little Entente was more than enough to serve its primary objective, that is to contain Hungary, I think that several realistic constraints of the countries and the alliance itself prevented them from being a credible force in defending against the Great Powers that could threaten its members.

Firstly, lines of communication and very shit between the countries. While they are all theoretically contiguous, the main land borders are in the underdeveloped Carpathians region, with the additional complexity of it being a mountain range. As far as I know, there are no railways between the countries that do not pass through others. That bodes really badly for a response against anyone that isn't Hungary, where the problem would solve itself.

Now, even handwaving that and assuming troop deployments could go flawlessly, would the countries really send their armies away? With their limited size and populations, they only have so many soldiers, and all of them have some threat to their own borders they can't afford to ignore. Can Romania really send soldiers to Yugoslavia when the Soviets could just decide it's a great moment to stake their claim to Bessarabia? And that same logic works for any situation, given that Czechoslovakia has Germany and Yugoslavia has Italy.

On top of that, the limited industrial capacity of the countries should be considered. While Czechoslovakia is the exception to this with a quite robust industrial base, I don't know if that is enough to supply everything Yugoslavia and Romania would need. That means that dealings with Great Powers are still necessary.

So, all that considered, could Yugoslavia be sure that with the Little Entente alone they'd have adequate support if Italy decides they want Dalmatia? Could Romania, if the Soviets decide to demand Bessarabia? The answer is a quite resolute no. That means that, at least for defending against other Great Powers, the countries of the Little Entente will still have to find themselves someone to support them.

On the subject of Italy, who are the top hypothetic pics as a successor to Mussolini in the 1930's? I know Italo Balbo and Dino Grandi (thank you, Hearts of Iron) but beyond those two and their associated ideological paths for Italy which seemed to both favour positive relations with Britain and France, I am not sure who else was present if Mussolini died or just in general as a counter-threat to him within Italy. I will need to write an Italy chapter soon and I know that Mussolini was quite paranoid about the Grand Council of Fascism replacing him.

Pretty much. Czechoslovakia has the best and the worst position, cause on one side it's the most self-sufficient of the bunch but on the other has no choice but to stick with France. For Yugoslavia France getting cozy with Italy would be a dealbreaker, and while Romania wouldn't take it badly, I could also see them doubting France's willingness to fight in Eastern Europe.That's a good point, I had forgotten about the fact that all of them have that fear of an enemy at their back if they go to help one-another. Of course, it wasn't helped by France's post-WW1 decision to turn inwards and build its fortifications instead of helping them to interconnect with each other and build a bullwark against Germany.

TheSpectacledCloth

Gone Fishin'

Count Ciano? Any of the Italian Field Marshals: Rodolfo Graziani, Pietro Badoglio or Emilio De Bono?On the subject of Italy, who are the top hypothetic pics as a successor to Mussolini in the 1930's? I know Italo Balbo and Dino Grandi (thank you, Hearts of Iron) but beyond those two and their associated ideological paths for Italy which seemed to both favour positive relations with Britain and France, I am not sure who else was present if Mussolini died or just in general as a counter-threat to him within Italy. I will need to write an Italy chapter soon and I know that Mussolini was quite paranoid about the Grand Council of Fascism replacing him.

Both Ciano and Balbo have connection and more importantly are in very good relations with the King and the royal family; frankly it's more probable a collective leadership by the Grand Council for a while till someone get the leadership position buuuuuuut without the big leader and the chaos in the Fascist Party the old enstablishement can see the occasion to reassert part of his power and influenceThat's a good point, I had forgotten about the fact that all of them have that fear of an enemy at their back if they go to help one-another. Of course, it wasn't helped by France's post-WW1 decision to turn inwards and build its fortifications instead of helping them to interconnect with each other and build a bullwark against Germany.

On the subject of Italy, who are the top hypothetic pics as a successor to Mussolini in the 1930's? I know Italo Balbo and Dino Grandi (thank you, Hearts of Iron) but beyond those two and their associated ideological paths for Italy which seemed to both favour positive relations with Britain and France, I am not sure who else was present if Mussolini died or just in general as a counter-threat to him within Italy. I will need to write an Italy chapter soon and I know that Mussolini was quite paranoid about the Grand Council of Fascism replacing him.

Here's a nice map that has both pre-ww1 borders and the interwar borders alike.That one is good, but I needed one that showed the modern nations seperate from one-another, which was harder

Garrison

Donor

Ciano might be the best choice, he could play to the Fascists and the old establishment to pull together some sort of coalition that keeps Blackshirts from creating trouble and give Italy breathing space to reorganize.Both Ciano and Balbo have connection and more importantly are in very good relations with the King and the royal family; frankly it's more probable a collective leadership by the Grand Council for a while till someone get the leadership position buuuuuuut without the big leader and the chaos in the Fascist Party the old enstablishement can see the occasion to reassert part of his power and influence

Marinetti?? Pareto? Gentile?That's a good point, I had forgotten about the fact that all of them have that fear of an enemy at their back if they go to help one-another. Of course, it wasn't helped by France's post-WW1 decision to turn inwards and build its fortifications instead of helping them to interconnect with each other and build a bullwark against Germany.

On the subject of Italy, who are the top hypothetic pics as a successor to Mussolini in the 1930's? I know Italo Balbo and Dino Grandi (thank you, Hearts of Iron) but beyond those two and their associated ideological paths for Italy which seemed to both favour positive relations with Britain and France, I am not sure who else was present if Mussolini died or just in general as a counter-threat to him within Italy. I will need to write an Italy chapter soon and I know that Mussolini was quite paranoid about the Grand Council of Fascism replacing him.

The riots are actually the focus of the next chapter in large part. They will stay mostly the same, with one divergence which will not become important until later on.Hi there, enjoyable timeline thus far. Looking forward to reading more of it.

Since France is coming up I wonder if the 6 Feb 1934 riots will see some changes?

Working on Chapter 13 right now, it should be done later today, in which case I will upload the France chapter today.

10 - La Sombre Époque

8mm to the Left: A World Without Hitler

"Sometimes I look around and wonder what the great kings and emperors of old would say about what France has become in the modern day. We are greater in some ways than they could ever have imagined possible, but the road to get there, the indignities and tragedies the French people have had to endure so that we could become the nation we are today… who’s to say if it was worth it?” - Maryvonne Darle, Prime Minister of France, 2002

La Sombre Époque

In the Northern part of Paris, near the centre of the Place de Républiques, there stands a statue representing the Third Republic alongside depictions of its sister republics. Like its sisters, the Third Republic is depicted as a woman. She is the epitome of contradictions, garbed in a flowing white dress with an infantryman’s kepi atop her head (the prevailing style following the Franco-Prussian War). Her hair runs wild and free across one shoulder, and over the other shoulder it is sheared close to the skull. In her left arm sits a book entitled “L’Aspiration”, and in her right hand she holds a sword into which the word “La Réalité” is engraved. The front fold of her dress is lifted, a military boot pressing down on a stone cracked in two. The word on that stone is “La Détente”.

The memory of the Third French Republic is a complicated one for the people of modern France, and it is not hard to see why. From its birth out of the fires of the Franco-Prussian War to its eventual demise, the Third Republic would represent both the tremendous heights of European civilisation as well as some of its deepest lows. The loss of Alsace and Lorraine to the new German Empire would define foreign policy for the nation and even their return in 1918 would not quell the ravenous hatred and, at its core, fear which the French felt for their more powerful neighbour. Despite how overwhelmingly this Germanophobia permeated the Republic, it would not define it. The end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries would come to be called “La Belle Époque” (The good era), the time of Europe’s greatest prosperity and influence across the world, a path paved by the British and French and their associated colonial empires. The Third Republic would extend the French influence and language across nearly every continent. France would be known as a nation of grand cultural and technological advancement and would stand above its many despotic neighbours as one of the few true nations ruled on the principles of equality, liberty, and justice.

In principle, at least. In practice, the Third Republic often failed to live up to the noble ideals on which it prided itself. Anti-German sentiment dominated the first half of the Republic’s life and made life harder for those of German, and often simply non-French descent. The most infamous of these cases was the Dreyfus Affair of the late 1800’s, wherein a Jewish soldier of Alsatian background found himself wrongfully accused and imprisoned for the crime of espionage, his status as a native German-speaker and his homeland’s recent annexation into the German Empire providing an easy explanation for his supposed treachery. It would not be until years later that the scandal would be made fully public, but its exposure would not have the delegitimizing effect on Anti-Semetism that so many had hoped for.

Much like its neighbours in Germany and Italy, the post-war years would see France struggle to balance rising political extremism and ethnic strife, both colonial and metropolitan in nature. The devastation wrought by the Imperial German Army on Northern and Eastern France had crippled the industrial regions of the Republic and further exacerbated the divide between the modern, industrialised Germany and the agricultural France. The post-war years saw heated debates lead to crises regarding everything from the reintegration of Alsace and Lorraine to pensions and governmental support for their veterans.

The first half of the 1920’s had been the roughest experienced by the French in a very long time, with inefficient taxation and widespread evasion making it difficult to gather funds and causing a growth in political extremism, namely the Communists on the Left and the Royalists on the Right. By the late 20’s this would have largely been rectified via reform and a massive reconstruction paid for with German loans, though it would not end the underlying class divide between rich and poor. The agricultural nature of France’s economy allowed it to ride out the Great Depression with relative stability, though it was not left completely untouched and the shockwaves would not dissipate for many years.

The reclamation of Alsace and Lorraine boosted the popularity of the Republic but it would soon become clear that these were not the same regions as the day they had been ripped from France in 1871. Beyond their reinforced German-speaking nature, the two had also grown accustomed to greater regional autonomy and a far more Conservative government, and chafed under the centralising, liberalising force of Paris. Soon after their annexation, the territories—renamed to Alsace and the Moselland—were granted greater autonomy within France as a counter to the voices proclaiming a desire to rejoin Germany. These laws would win the loyalty of Alsace but cause strife in regions where such privileges were envied.

Far more than Alsace and Lorraine, though, remained the question of the colonies. The 1920’s and 30’s saw the peak of France’s expansion until that point in history, from the French Caribbean in the West all the way to Vietnam and Tahiti in the Far East, and though the British Empire remained the preeminent world power, France did not linger far behind. France had long sought to instil in its overseas subjects the notion of a “Unifying France”, one whose superior values, culture, and language would not only bring civilization to the so-called “primitives”, but which would ideally also bind them together in a collective union led from Paris. A grand sentiment, if one often at odds with the emerging sense of Nationalism across the colonised world.

The oldest of France’s African colonies, Algeria, would serve as a makeshift petri dish for many of these ideas. Originally a colony of France from 1830 to 1848, Algeria would soon after be annexed directly into France proper where it would face extensive Francisation policies. French colonists would be encouraged to immigrate, French would replace the regional Berber and Arabic dialects, Islam would be repressed in favour of Catholicism, and citizenship would be reserved for a minority while the non-white Muslim and Berber majority would be considered merely French nationals rather than full citizens. While legally and bureaucratically a full constituent part of the Republic, the mistreatment of the natives and French xenophobia would remain a perpetual thorn in the side of Franco-Algerian relations.

French Algeria c. 1930

(https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Algérie_1830-1930.JPG)

The Third Republic’s foreign policy before the Great War had been dominated by its revanchism against the German Empire, and even after the Great War and the restoration of the territories lost in 1871, fear of German aggression continued to dominate both domestic and international policy decisions. Immediately following the Great War, France had sought to build ties with the new emergent nations, in particular Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia, whom the Third Republic saw as natural allies against future German expansion in Europe. Historic ties with Russia would lead to the French building bridges—albeit hesitantly—with the new Soviet Union, though it would damage their ties to the so-called “Little Entente” when it was feared that France might sacrifice her Eastern allies in order to gain Soviet aid. A similarly contentious connection was that between France and Fascist Italy. Mussolini disliked France for their betrayal during the post-war negotiations, failing to back Italian claims in Austria-Hungary and Turkey, and had previously expressed interest in historically-Italian lands owned by France. Despite this, he was open to cooperation with France—for a price—and an alliance with the Italians was seen by many in the military as preferable to one with the Soviets.

Fear of Communism was a potent rallying force for Right-wing parties within the Third Republic, in large part because France remained one of the few European countries where Communist ideology was allowed its voice on the national stage. France would come to be one of the great centres for Communist philosophising in the Western World and would, over the years, attract leading Communist minds, including most famously Leon Trotsky, former heir-to-Vladimir-Lenin-turned-exile following Stalin’s seizure of power in the Soviet Union.

The presence of so many Communists, many of whom ideological exiles from nations like Italy and, following von Lettow-Vorbeck’s ban on Communism, Germany, worried many French politicians, who saw this rise as a sign of Soviet attempts to manipulate France and, at worst, transform it into a puppet state of Moscow.

Anti-Communist propaganda from France; “It is the Communists who pull the strings of the Popular Front”

(https://www.imago-images.de/st/0095422539)

By the beginning of 1934, the scales had begun to tip away from the historically-popular Left-wing parties, embodied by the Cartel des Gauches (Cartel of the Left) government which had been elected in 1932 but which lacked the absolute majority needed to cement their power. An inability to form a cohesive coalition would lead to several of these Centre-Left governments falling in quick succession and, though they would retain power, their ability to affect change would be greatly diminished, especially with a rising wave of Right-wing extremism in response to the growing public discomfort at the strength of the Communist movement. The rising tension would finally erupt in February of 1934 following the so-called “Stavisky Affair”.

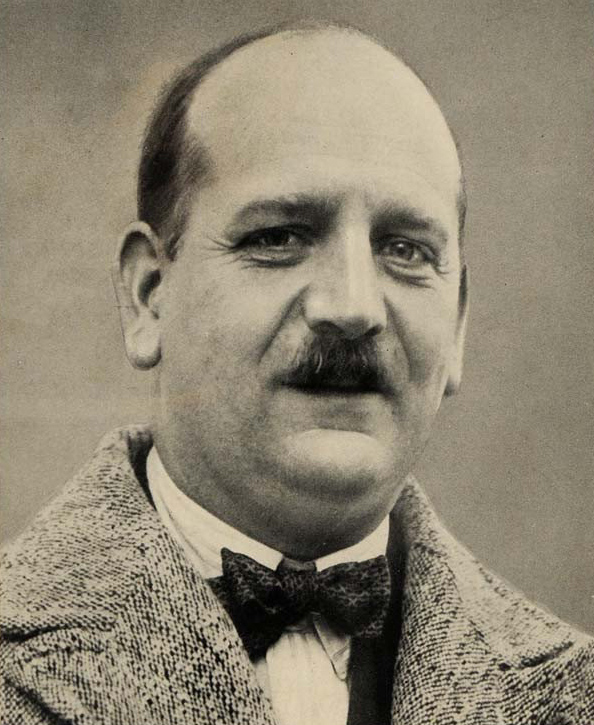

Serge Alexandre Stavisky

(https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipe...visky_-_Police_Magazine_-_14_janvier_1934.png)

Serge Alexandre Stavisky was a naturalised Russian-Ukrainian Jew who had grown up in France after his parents emigrated from the Russian Empire. He had risen to fame and later infamy through a series of extensive embezzlement scams and schemes, including, most famously, selling emeralds which had supposedly once belonged to the Empress of Germany, but which had turned out to only be glass. He built around himself a network of friends and connections within the wealthiest and most powerful of France, using a combination of their influence as well as his own wealth to ensure that his actions were not made known to the greater public. It was not until 1927 that he would at last be exposed and put on trial, only for the trial to be postponed multiple times, during which Stavisky remained out of jail on bail. It would not be until his death in early January, 1934—ostensibly suicide but suspected of being the work of the police who found his body—that the full extent of his crimes would come out.

Stavisky’s death would open a proverbial Pandora’s Box of secrets as men up and down the rungs of power had their connections to him exposed. The most galling of these was his close connection to the cabinet of Prime Minister Camille Chautemps, having had close ties with two of the leading Ministers. The situation further unravelled when the press revealed that the 19-month postponement of Stavisky’s trial had been due to the public prosecutor being Chautemps’s brother-in-law. Public opinion swung violently against the Prime Minister and questions were quickly raised as to Chautemps’s culpability in Stavisky’s death, and whether or not it had truly been suicide. French Right-wing groups led the charge against the Prime Minister, accusing him of having arranged the assassination of Stavisky to keep his secrets from coming out, and the outrage was inflamed to such levels that Chautemps was finally forced to resign at the end of January.

He was soon succeeded by Édouard Daladier, another politician of the Radical-Socialist Party. Daladier understood the goals of the rioters to be the toppling of the Centre-Left government and the installation of a Right-wing one, and so took immediate action against them. The most significant and damaging steps he took was the dismissal of Jean Chiappe, the head of the Parisian police, whose famed Right-wing sympathies and suspicion in previous anti-governmental movements had led Daladier to suspect Chiappe’s involvement in the riots and him being the reason that they had grown so out-of-control. Daladier compounded this with the appointment of a new Interior Minister, Eugène Frot, thereby bringing control over the Parisian and greater French police under party control. Frot would be quick to take action against the protests and would decree that any protestors would be shot by police.

Soon after, the centre of Paris erupted into chaos.

Prime Minister Daladier hurried through the hallways of the Hôtel Matignon, a swarm of secretaries following after him while also trying not to bump into the three security guards surrounding him at all times. These were dangerous times, after all. He scribbled an illegible signature across one of the documents presented him before looking around wildly, cursing under his breath.

“For heavens’ sake, where is Monsieur Frot?” he demanded loudly, uncaring as to who answered him as long as someone did. “I need to know what is going on at the Bourbon Palace!”

“Monsieur Frot is currently trying to redirect forces from South Paris,” one of the aides at his right told him, her hair jumping up and down as she all but ran to keep up with the man’s pace. “The riots are smaller there and the troops better-suited at the National Assembly.”

“That, at least, is something,” Daladier declared, turning to the man on his left. “Is there any news from the Assembly?”

“Fighting broke out between deputies sympathetic to the strikers and to the government. The guards were forced to intervene and the session was ended until these riots can be brought to heel.” He hesitated. “Some are calling for a vote to dissolve the current parliament.”

“They will not get it!” Daladier bellowed, stopping suddenly and nearly causing the rest of his group to collide with him. “If we give in to these agents of chaos, we are all but proving to the world that the Republic is unstable! We will fight these savages like we fought the Barbary pirates. They will give in or they will be crushed!”

He continued on and at last reached his office and entered, the aides scurrying off to their tasks while the guards took their posts outside the doors. Daladier crossed to his desk but did not sit down, instead snatching the phone and dialing in the number for the Interior Ministry. It rang briefly before dropping, indicating that Frot was still preoccupied. Daladier scowled and all but slammed it down, crossing to the window. The riots were not visible from the Hôtel Matignon, but neither were they far, and Daladier imagined that, if he strained his ears, he would be able to hear the rumbles of boots on stone and men yelling.

“Maudits fascistes!” he swore loudly. He likewise cursed that fool Chautemps and the whole mess with Stavisky. Their idiocy threatened to bring down the whole government! Daladier was no Communist, but he would choose Stalin every day before he saw France slip into the stagnation of monarchy once again; or, worse, fascism.

This could not possibly have occurred at a worse time. The Germans had slithered out of their post-war stipulations and their rising economy was hurting French morale. They were la belle nation, the very foundation of European culture and beauty, how could the Germans again be outstripping them? And with another Prussian at its head, it would only be a matter of time before the Germans once again tried to conquer Europe. France had to be strong, to be united, and the Republic was the only way to do so.

Out of nowhere his phone began to ring and Daladier all but flew across the room to grab it. “Oui?”

“It is Frot.” The voice on the other end of the line was dry and raspy, and Daladier’s heart sank when he heard it.

“What is it? Has the Assembly fallen?”

“No, sir, but it may be worse. François de la Rocque has been killed.”

Daladier gripped the phone with both hands. “What!?” he hissed. His mind began to race. De la Rocque was the leader of the Croix de Feu (Cross of Fire) veterans’ league, one comprised overwhelmingly of Right-wing members. It was not the largest of the groups, but it had broad sympathy among much of the population who revered the veterans for their role in the Great War. De la Rocque’s death would look bad, there was no doubt about it, but it was not unsalvageable. He was only one small piece. “What has been the reaction?”

“None so far, sir. Several members have attacked the barricades but they seem to have pulled back overall, allowing us to redirect forces from the South. We are unsure if anyone has stepped up to replace him or if the group will splinter.”

“Keep an eye on it,” Daladier ordered. “Protect the Assembly at all costs! They must not be allowed in!”

“Yes, sir.”

The call ended and Daladier stared at the receiver for a moment. De la Rocque had been the binding force of the Croix de Feu. As far as Daladier knew, the man had never shared power nor attempted to reform the group into much of a threat. His death could only be a good thing.

Right?

“Who takes over now?” was the question spoken by many as they gathered under several trees along the Seine. It was the wee hours of the morning and the riots had calmed (though not abated) as many broke to eat or rest. None of the groups had yet been able to break the barricades and reach the Assembly, but likewise, the police had not been able to disperse the group. Now the Croix de Feu was beginning to shed, members breaking off in groups to discuss what they should do now. Some had already left, feeling their cause lost without their leader.

“I say we quit,” declared a younger man with a short beard. His eyes were lined with circles and his expression seemed etched in a perpetually sour shape. “We tried, we failed, let’s get out of here before they come for us, too.”

“Have you no love for your nation?” demanded an older red-headed soldier, baring his teeth. “We fought for France against les boches, we will do so against against the vile Reds!”

The younger gestured aggressively, saying, “I’ve fought enough, I will not risk ending up like de la Rocque! I have a wife and a son on the way!”

“You should think of your son, then,” another chimed in, “do you want to see him grow up a slave to Moscow?”

“Better than growing up without a father!” the first shot back.

“Quiet, both of you!” the oldest of the group ordered. He ran his fingers through his bushy beard. “I will take over for de la Rocque. I am the one with the highest military rank.”

A guffaw was his response from the red-head. “You fought in Cameroon, leading a pack of monkeys doesn’t count!”

“They were better fighters than anything I saw today!”

“Well I did not see you leading the charge!”

“That’s it! I’m done!” announced the young bearded man, rising to his feet. “You lot can stay here with the other fools and die for nothing. I would rather live to see another sunrise!” He moved to walk off, but then a voice spoke.

“Would you not rather live to see a new, brighter France for us all?”

The group turned to see a duo step into the light of the streetlamp. Several of the group members’ eyes widened at the sight of the shorter, bearded member of the duo, though he was not the one who spoke. “This is Charles Maurras,” introduced his companion, a tall clean-shaven man in a suit, as he gestured at the other. “I believe you will want to hear what he has to say.”

“I know you!” exclaimed the oldest with awe in his voice. “You are the founder of the Action Française!” His companions, recognising the newspaper and the party associated with it, likewise turned in shock.

Maurras did not speak, but instead began a series of quick gestures which baffled the onlookers. His companion seemed to understand them, though, as he soon spoke. “I am, but do not think of me as such. I am merely a man with a love of France and its people. I am saddened to see what our great nation has fallen to, the work of traitors and fools who fail to do what needs to be done.”

“Well what can we do?” asked the red-headed man, looking between the two. “The government doesn’t listen to us and the police killed our leader!”

“The loss of de la Rocque was a tragedy,” communicated Maurras through his interpreter, “and it was what brought me here today. To see so many good, noble, honourable Frenchmen fighting for what they believe in, it warms my heart. You have lost your leader, but not your fire.”

The compliments had the desired effect and the men stood a bit straighter, even the one who had been ready to walk off. “Fire will not win us this,” he said. “This is not 1848. We cannot win.”

“It is irrelevant whether or not we win on the streets of Paris. We must win in the hearts and minds of men.” Maurras’s eyes seemed to almost glow in the reflection of the lights. “They see us and they feel for us. For the Croix de Feu, the noble men who defended us in 1914, who are now attacked and killed by the police. And why? For demanding that their nation hears their suffering and their desire to protect the ones they love? That is not justice, that is tyranny! Join with us, with the Action Française, and help us win the fight against those who would oppress France. Even if we do not win by force of arms today, mark my words, they will learn to fear us.”

The February 6 Uprising’s success or failure is largely dependent on how one approaches the results. On the one hand, the Uprising failed to achieve its largest goal, that being the end of Centre-Leftist rule over the National Assembly and possibly even the end of the Republic in favour of a dictatorship. On the other hand, it did succeed in many smaller goals. Many within the police and government refused to abide by Daladier's attempts to viciously crack down on the protestors and it led to a rapid delegitimizing of his power base, so much so that he would be forced to resign on the 9th when it became clear that he would be unable to manage his government. His replacement, Gaston Doumergue of the Centre-Right Radical Republicans, would begin the slow shift away from the Centre-Left.

Gaston Doumergue

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaston_Doumergue#/media/File:Gaston_Doumergue_1924_crop.jpg)

The death of Colonel François de la Rocque and the power vacuum which emerged in the Croix de Feu, the most important league by membership numbers, triggered a domino effect which ended with the group’s new leadership forming a coalition with and, later, fully merging with the Action Française later in 1933. This new coalition was a powerful force for opponents of the Third Republic and frustrating adversary for the Cartel des Gauches.

In the wake of the February 6 Uprising, many in France would see the act as an attempt by Fascist sympathisers to overthrow the Republic and establish a dictatorship. The Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes (Watchfulness Committee of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals), or CVIA, would be established by concerned citizens to combat perceived Fascist infiltration within the Third Republic. This group’s popularity is indicative of the general feeling within France; while many were unhappy with the Third Republic and felt that the system needed to be changed, the advocates for a true dictatorship were far fewer.

Action Française would spend much of 1934 and 1935 dealing with growing pains following its absorption of the Croix de Feux and the need to reconcile the various different groups within itself. Fascism and Monarchism were two of the leading forces, but a not-insignificant minority advocated for a form of Authoritarian Democracy not entirely unlike what had been achieved in Germany under Chancellor Brüning and President von Hindenburg. These divisions were not so insurmountable as to rupture the coalition, but likewise too significant to provide a united front, and in the end it was these divisions which kept Action Française from seizing the power it would have needed to gain control over the National Assembly and elect one of their own into power.

Across the Alps, Mussolini would watch the transition within France with curiosity and interest. Though Italian Nationalists viewed the French lands of Savoy, Nice, Tunisia, and especially Corsica with hunger, it was also well-understood that Italy could not simply take these lands—or the others they desired—without the aid of another Great Power. An alliance with France brought with it many benefits, including the prevention of a two-front war and the reassurance which was the large French navy. Additionally, like Italy, France viewed Germany as the most significant threat to their influence, as while Italy concerned itself with Austria and the Balkans, France sat directly on the German front-line. French guarantees would be useful in ensuring Viennese submission to Rome and would make it easier to force territorial revisions in strategic regions, such as Yugoslavia.

The French government under Doumergue would last less than a year and would attempt to reconcile the extremist forces within their nation, carving a centrist past between the Stalinist Left and the pseudo-fascist Right. Though his attempts were noble, in the long run Doumergue would prove ill-equipped to balance the powerful opposing forces, and upon his resignation in November, the French government would have shifted fully into the Centre-Right, epitomised by his replacement, Pierre-Étienne Flandin, who would hold the office until the next election in 1936. Flandin’s willingness to cooperate with the Italians and, by early 1936 shortly before the election, his willingness to turn a blind eye to members of the Action Française to leading roles within the government, made many within Germany and Spain fear the rise of a Franco-Italian alignment capable of threatening all who would oppose them.

Pierre-Étienne Flandin

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre-Étienne_Flandin#/media/File

The eventual end of the Third French Republic was predicted by many of the most astute politicians of the time, and with the benefit of hindsight, is often seen as an inevitability. Others argue the opposite; though openly sympathetic to the anti-Republican forces within the government, it was neither Doumergue nor Flandin onto whom the blame for the Third Republic's future fall can be fully laid. It was not until 1936 that France's path was cemented, and with it, the millions of innocents whose blood would eternally drench French hands.

Last edited:

I am not sure how well I captured it, but I wanted this chapter to sort of be a parallel to the divergence which was caused by Hitler's death in Germany. Now, one of France's lead anti-democratic figures has died, but the effects it has on France will be vastly different.

bit anachronistic, all phones had dials at this timeinstead snatching the phone and putting in the number for the Interior Ministry.

so better would be:

instead snatching the phone and dialling the number for the Interior Ministry.

overall nice update

I figured that putting would be less anachronastic, somehow I forgot that the rotating phone was actually called a dial so dialing would make more sense, hahabit anachronistic, all phones had dials at this time

so better would be:

overall nice update

Share: