8mm to the Left: A World Without Hitler

"I looked across that short stretch of road to my homeland, to my empire, and I wept… how could it have come to this? How could my people have betrayed me so easily? A kingdom, an empire built by generations of great von Hohenzollern kings… could it really be ending here, now, with me?” - Excerpt from the memoirs of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, c. 1937

The August Crisis

On August 2nd, 1934, former German President Paul von Hindenburg passed away at the age of 86 years old. The news of his death, more than the death of any other high-profile war hero, was marred by controversy surrounding his tenure as President, his association with Brüning, and of course the

Osthilfeskandal in which his family estate played a significant role. Expressions of pity and sympathy for his family were the rote line of the day, but one did not need to listen hard to hear the murmurs under the surface, the frustration and at times even hatred for the man’s rule which was now translating itself into elation at his death.

Von Hindenburg's passing was the final major pillar in the progressive loss of all the so-called “Old Prussians”, the politicians and generals who had been around since the days before the German Empire and who had stood as the Conservative bastions against ideas of Liberalism and Democracy. Von Hindenburg had been one of the last and, with him gone, the influence of the Old Prussians was at last fading.

President von Lettow-Vorbeck was not a true Old Prussian—he had not come into adulthood until the Empire was well-established—but he considered himself a curator of their legacy and the legacy of the Kaiserreich as a whole. As such, he felt that it was his duty to ensure that one of the heroes of the Great War was given a proper send-off. This was supported by the majority of his government with even Adenauer, a vocal critic of the former President, admitting that it would, at least, be a media boost to show one’s respect for a former leader.

Behind the scenes, though, von Lettow-Vorbeck had more politically charged-motivations than mere patriotism. On the day after von Hindenburg's death, he would have a brief and unrecorded meeting with Kurt von Schleicher, during which the duo conspired to use the upcoming ceremony to fulfil their own political desires.

Cecilienhof Palace was a beautiful, sprawling estate located near Potsdam, in the state of Brandenburg, not far from Berlin. It was a beautiful country home done in an English style with heavy Tudor influence, a gift from the last German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, to his son and heir Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. The palace was named in honour of the Crown Prince’s wife, Duchess Cecilie von Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and had served as one of the main residences of the royal family. Following the revolution which overthrew the monarchy, an attempt had been made to expropriate the properties and finances of the former ruling families, but the vote to this effect had come back in favour of the monarchs. Since then, the imperial von Hohenzollern family had retained many of their properties, and Cecilienhof, though remaining in state ownership, had been opened for residence to Wilhelm and Cecilie for themselves, their children, and their grandchildren.

Cecilienhof Palace

(https://www.visitberlin.de/system/f...ock_c_MagMos_web.jpg?h=1c9b88c9&itok=EMLFEMDH)

Though beautiful in any season, it was during Autumn when the palace truly looked its best, thought Kurt von Schleicher as his car rumbled its way up the drive towards the building. The changing of the trees offset the beiges and browns of the exterior beautifully and he could already picture the former Crown Prince crashing through the brush on horseback alongside his sons.

Von Schleicher parked his car near the front door and a valet quickly hurried over to take care of it, the Minister of Defence handing over the keys without a glance. He was well-known by the servants and staff of the estate; he had spent enough time here even before his ascendance in government for them to remember his patterns.

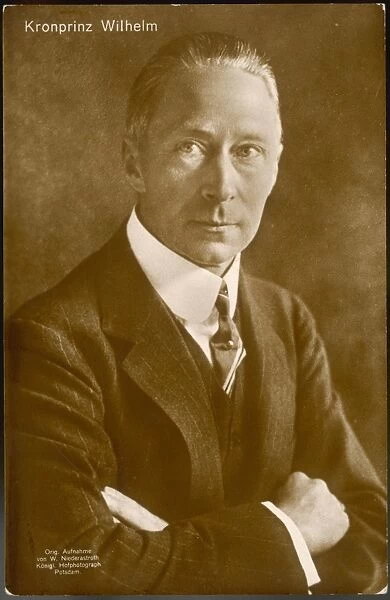

A figure was standing on the porch as von Schleicher strode forward. Perfect posture, handsome features, and an aura which positively oozed status, it was difficult for anyone to mistake Crown Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern as anything but a royal. The man raised one eyebrow as von Schleicher approached, unclasping his hands from behind his back. “You are late,” Wilhelm declared with a teasing little lilt to his voice. He offered a hand, which von Schleicher grasped familiarly.

Crown Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern, son of Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1934

(https://www.prints-online.com/crown-prince-wilhelm-597312.html)

“Dreadful traffic heading towards Potsdam,” he answered. “They are talking of widening the Potsdam-Berlin Autobahn to accommodate for the traffic.”

“So soon?” said Wilhelm, surprised. “Was it not only finished in March?”

“An unexpected surge in use. Have you heard of the Porsche plans for a cheaper car aimed at the middle class? If they go forward and succeed with it, we might see twice the cars in just two years’ time.”

“I have indeed read about it. What an inspiring time to be alive.” The Crown Prince beckoned the other man inside and they entered the palace. The tall, sweeping foyer was decorated in warm colours, electric lights placed in tasteful wall sconces to give the room a feeling of modern regality. They passed through an archway and down a hallway towards Wilhelm’s personal study, passing a few paintings undoubtedly worth more than all of von Schleicher’s earnings combined. Once they were inside the study, Wilhelm closed the doors behind him and directed them to the leather chairs tucked in the corner by the bookshelves. “What did you wish to speak with me about oh-so-urgently?” He grabbed a cedar box and popped the lid, holding it out. “Cigar?”

Von Schleicher could not resist taking one, lighting it and taking a drag. It was the expensive sort, probably Cuban. There were perks to being friends with a wealthy member of the ex-nobility. “You are no doubt aware of General von Hindenburg’s passing?”

“Naturally.” Having taken his own cigar, Wilhelm snapped the box shut. “The funeral will be a public affair, of course.”

“Of course. The ceremony will begin at the Reichstag, pass through the Brandenburg Gate, up Unter den Linden and past the imperial palace, and end at the cathedral. He is being given the full pomp and circumstance owed to an imperial general—President von Lettow-Vorbeck ensured it personally.”

The Crown Prince rolled the still-unlit cigar between his fingers, eying it thoughtfully. “It is a shame that such a valued and decorated member of the Imperial Army cannot be properly honoured by a member of the royal family. It is the least which he has deserved for his service to the crown.”

Von Schleicher knew what his friend was getting at. “I am aware of your father’s request that his exile be temporarily lifted so that he might attend. You understand that such a thing would be impossible.”

“I do.”

“It is more than just the French or British. Berlin is much-changed since he was last there and he is a contentious figure at the best of times, as was von Hindenburg. We have already been forced to prepare contingencies for possible protests or attacks. It would not be wise to stir the pot any more than has been done. The last thing Europe needs is another monarch to be assassinated, even a retired one.”

“Kurt.” Wilhelm held up a hand, stopping his friend with a gentle smile. “I understand. More so than my father, anyway.” His smile turned a bit bitter as he spoke of the last Kaiser. “Father has become… agitated. Irritable, perhaps, is the better name for it. He seems to have had other expectations of von Hindenburg and von Lettow-Vorbeck, unrealistic expectations which have naturally been left unfulfilled. He simultaneously praises the actions taken against the Socialists while cursing what he sees as infringements on German honour. The last time we visited, he spent nearly three hours lecturing us on his geopolitical views prior to 1914 and defending every step he took. He demands to know why the monarchy has not yet been restored. He refuses to consider the realities of the situation. When I told him point-blank that the German people would never accept him as their ruler, he threw me out of the house.” He shook his head. “I don’t know what to do with him.”

Von Schleicher said nothing. Much as he respected Wilhelm II on the basis of his noble heritage, his personal view was that the man had played a large part in the circumstances which led to German humiliation at the hands of the Entente. The institution of the monarchy was the backbone of cultural pride, but that did not mean that a king should be allowed to run rampant; no, better to condense the power in the hands of a skilled Chancellor or Prime Minister, as the Italians had done, while protecting the king from the backlash.

While von Schleicher was mulling this over, the Crown Prince at last set about clipping and lighting his cigar. The smell of rich tobacco blended well with the cosy, musty smell of old books and stained wood. “Tell me honestly, Kurt,” he spoke after several minutes of comfortable silence, “do you believe that our family will ever again regain the throne of Prussia?”

The other man considered it. It was a question which he had mulled over to himself many times, though less so recently. “I believe that the likelihood of it today is greater than it has been in a very long time, but lesser than is necessary to accomplish it,” he decided on at last. “Von Lettow-Vorbeck is a supporter of the idea, make no mistake. He would do it now if he could, but he is not so short-sighted. His hold on the German people is strong, but not all-encompassing; Leftist ideas still permeate and Prussia remains under Socialist thrall. Without Prussia, we have no chance.” Von Schleicher’s eyes turned sharp. “The days of a monarchy like that of the old Empire are dead, though. A new German Empire must be strong and united to retake its place in Europe, not a broken federation like we were.”

Disagreement flickered behind Wilhelm’s eyes but he did not say anything. They had had this debate many times before and it never saw a proper resolution, Wilhelm a defender of the old system and von Schleicher advocating something new and modernised. “Is that why you came here, then? To debate politics with me?”

“Ah. No.” Von Schleicher tapped the ash of his cigar into a nearby porcelain ashtray engraved with the Prussian eagle. “As we have discussed, your father will be unable to attend the funeral. However, von Lettow-Vorbeck has personally requested your presence in his place, as representative of the von Hohenzollerns, to help lay the General to rest.”

Wilhelm’s eyebrows rose. It had been clear that this request would have something to do with the funeral, but he had been anticipating a request to steer clear of it, not to attend. “My appearance alongside the President and Chancellor would be… contentious, as you put it. Was that not something which you were trying to avoid?”

“There is rocking the boat and there is overturning it. Your appearance would be as a private citizen connected to von Hindenburg through personal connections. No statements will be made and any conclusions drawn will be unsubstantiated.” He leaned forward. “I told you that the President is supportive of our goals to see the monarchy restored. The support of the people is paramount; this is the first step.”

Prince Wilhelm was clearly dubious, though not uninterested. “You do not think that my presence would be seen as… improper?”

“Let us worry about that. We wish to build a new, better Germany, built on the ashes of this broken Republic; you cannot make an omelette without breaking a few eggs.”

Prince Wilhelm’s arrival in Berlin on the day of the funeral, the 7th of August, was a complete surprise to most onlookers. Aside from Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and the von Hindenburg family (whose approval had been necessary on the basis of politeness alone), no one had been told about the appearance of one of the members of the former imperial family. Even Martha von Lettow-Vorbeck, so rarely not privy to her husband’s thoughts, was reportedly stunned at the arrival of a von Hohenzollern shortly before the service began.

The former Crown Prince was seated in the front row of the church at the innermost end of the pew, directly beside Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and in front of Konrad Adenauer. Adenauer spent the entire service glaring daggers at the back of Wilhelm’s head, though the supreme dislike in his stare went largely ignored by Wilhelm and the president. While there was a clear undercurrent of curiosity and surprise at the presence of a von Hohenzollern (at least amongst those who recognised him), it thankfully did not cause a stir or provide too major a distraction, something which the von Hindenburgs had been worried about. After all, Paul von Hindenburg’s loyalty to the German Empire was something which had been used to praise or ridicule him throughout his entire rule; it was not strange that such loyalty would be remembered.

What

did surprise the onlookers was that, when the time came to make speeches on the achievements and character of the former president, it was Prince Wilhelm who was selected to give the first speech, preceding even the minister and the man’s family. Since the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and his family’s loss of their noble titles, the status of the Kaiser as Head of the Protestant Church had been abolished, and decorum would demand that the clerical member speak first. Giving Wilhelm such flagrant privilege was both a return to old precedent and a test of public reaction.

“I recall the day I first met President von Hindenburg, then a general in the Imperial German Army,” Prince Wilhelm began. Though he had lost his crown, he spoke like a man raised to present before an adoring population, each word clear and booming through the Cathedral of Berlin. “I was a lad of only six or seven at the time, still frightened by artillery and machinery of combat. My father, freshly-crowned Kaiser Wilhelm II, wished for me to better understand the military of the nation I was to lead, and so requested that one of his leading generals introduce me to the fundamentals.” His lips quirked in amusement. “Few were particularly gifted with children, nor was teaching within their realm of expertise. It was only General von Hindenburg who took to the request eagerly. Over the two weeks I would spend in his company, he would impress upon me not only the importance of our military power, but our history and legacy. He took me to Schleswig to examine the viking Danewerk and show me the importance of maintaining good defences. He took me to Lorraine and showed me the path our armies carved through the French in 1871. He even brought me across the border into Belgium, to show me Waterloo and walk me through every hour of Napoleon’s defeat.”

The church was completely silent, all hooked on the speech.

“Though we had little contact in the years after this, Paul von Hindenburg has remained ever since the embodiment of a good Prussian in my mind: Strong, intelligent, and unyielding, while simultaneously helpful and caring for those close to him.” Here Wilhelm nodded to von Hindenburg’s grandchildren, seated in the front row. “His loyalty to the German people was second to none, even sacrificing his retirement following the Great War to serve Germany as her president. President Paul von Hindenburg is a man whose legacy will live on for as long as the Reich stands along the names of Bismarck and Wilhelm I. Today we mourn his loss, but tomorrow we will honour his legacy by working towards the Germany he envisioned for us all.”

Once it became clear that the speech had come to a close, President von Lettow-Vorbeck began to clap. A half-second later his clapping was joined by the von Hindenburg family, and it was not long before the entire church was clapping as Prince Wilhelm descended the pulpit and returned to his seat. Once again, a breach of tradition in cheering at a funeral, and more than a few raised eyebrows and glances were traded, but no one knew what to say and so kept quiet.

The next few speeches were more along the lines of what people expected, short personal anecdotes from the minister, Oskar von Hindenburg, and several of President von Hindenburg’s closest friends. None of them received applause, and consequently it was Prince Wilhelm’s speech which people remembered most and which they would go home to tell their families and friends about. No burial was to be held in Berlin, despite the offer of a memorial in the military cemetery by President von Lettow-Vorbeck. The family had graciously declined, and in accordance with the man’s Last Will and Testament, his remains were to be transferred to Hannover, where they would be interred at his family plot. (1)

Upon getting into the car to drive home, Martha von Lettow-Vorbeck turned and gave her husband a shrewd look. “How long were you planning that, then?”

“Only a few days,” von Lettow-Vorbeck answered truthfully. “It felt like the opportune time to reintroduce Prince Wilhelm.”

Martha

hmm’d. “Some might take it as a sign of disrespect,” she warned, “using a funeral to introduce political allies. Adenauer was positively spitting fire by the end of the prince’s speech.”

“I indeed felt him spitting something on the back of my neck, though I rather doubt that it was fire,” the man joked lightly. In the back seat, the two boys giggled.

Martha was not impressed. “Laugh all you want, but be careful with him,” she warned. “Adenauer is a political animal.”

“I know,” her husband replied, this time seriously. “I consider it a calculated risk. Adenauer is growing a bit too comfortable with the influence I have granted him. We share many beliefs, but there are points on which I will not waiver, and he must be brought to an understanding on that. He will be angry, but he cannot truly seek to oppose me over a private citizen speaking at a revered general’s funeral. It would make him seem paranoid. And the only significant threat who would back him in the Reichstag is the SPD, and siding with them over the matter would be political suicide.”

“You’ve really planned this out,” Martha noted in surprise.

“Of course, my dear. This job has forced me to evolve my way of thinking, but I am nothing if not adaptable. And in truth, people remain as they are, be they soldiers or politicians. And people are something I have great experience with.”

The question of the former German nobility had been an early and significant problem for the German Republic, given that the German Empire had possessed within it the largest collection of kings, princes, and dukes in all of Western Europe, including branches of foreign royal houses. Even following the abdication of the various rulers, the noble houses retained their control over wide swathes of land, virtual treasure troves of finances, and centuries of priceless art and cultural artefacts which many in the new German Republic felt should belong to the people, not to distant and now-deposed nobles.

During the early 1920’s, the overall policy of the Republican government had been to leave the matter of the nobles to their individual states, as the question of royal properties was more important to some than others. In Mecklenburg-Strelitz, one of the smallest Free States, the land claimed by the nobility was over half of the overall territory, while in larger states such as Prussia the amount was far more negligible. Despite the economic importance of those lands to their individual regions, in most cases attempts to claim the land by the state failed, usually owing to the predominantly Conservative and monarchist viewpoints of the judges who were to decide the constitutionality of such expropriations. This failure on a regional level frustrated many Left-wing politicians and, in 1926, the German Communist Party proposed a nation-wide referendum on seizing the property of all royal houses throughout the entirety of Germany. Following the economic downturn of the time and the general public debt, the Communists banked on public discontent working in their favour against the remains of the royalist establishment.

Pro-Expropriation Propaganda: “Not a penny for the princes! They have enough! Save the people 2 billion!”

(https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expropriation_of_the_Princes_in_the_Weimar_Republic)

Despite the Communists’ attempts, the referendum would fail, owing to additional hurdles added by President von Hindenburg as well as an extensive mobilisation by Conservative parties against the action, not to mention support from the Catholic Church which feared this being a precursor to the seizure of Church lands. With the referendum’s failure, the situation of the various royals—in particular the von Hohenzollern family, Germany’s rulers from 1871 until 1918—improved tremendously. With the majority of their wealth and major holdings retained, they would continue to claim the German and Prussian thrones and advocate for the restoration of the monarchy throughout the 1920’s, supported heavily by the landowning Junkers and various Conservative politicians such as von Hindenburg, with Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern even being considered as a presidential candidate for the 1932 election before von Lettow-Vorbeck emerged as the better option.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck was a monarchist through and through, and even before he had assumed the presidency he had been making plans with Kurt von Schleicher for how to best approach his goal of returning the Kaiser to his throne. Even after he became president, this path to this goal would not be a clear one; Kaiser Wilhelm II’s poor wartime leadership and flight to the Netherlands from the defeated Germany had not endeared many people to the institution of the monarchy, and for all that the Weimar Republic had its critics, those critics were split on the matter of a new Empire under a king or under a dictator. Thus, von Lettow-Vorbeck was forced to put these plans on hold until such a time that he could begin taking steps in that direction.

The first of these steps was the so-called August Crisis of 1934, triggered when Prince Wilhelm, the heir to the German throne, was brought into Berlin by von Schleicher to make a speech at President von Hindenburg’s funeral. This event itself was small, but would trigger a crisis of enormous impact in German history.

Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, despite his party’s tacit support for the monarchy, was a long-time opponent of it, seeing it as a threat to Germany’s attempts to integrate more heavily with the rest of Europe, as well as holding a deep personal distaste for the von Hohenzollerns. Though working semi-amiably with von Lettow-Vorbeck, the duo had often clashed over their ideological visions for Germany. Before August 7th, 1934, Adenauer had believed that von Lettow-Vorbeck’s Monarchism was a matter of character; now, he saw it for the threat it was and decided to take decisive action to cut it off at the knees. In a striking display of political subterfuge (the details of which would not be discovered until years later), Adenauer reached out to his long-time political rival, Otto Wels of the SPD, and urged him to take rapid and decisive action.

On August 10th, the SPD party newspaper

Vorwärts released a blistering attack against President von Lettow-Vorbeck and Minister Kurt von Schleicher, accusing the both of them of “conspiring to overthrow the German Republic and restore the Kaiser”. Alongside photographs of the trio exiting the Berlin Cathedral were passages warning of Conservative-monarchist plans to invade France and trigger a second Great War. The claims might normally have ended there, but soon—ostensibly due to Adenauer’s influence, though evidence of this is largely circumstantial—this story would be picked up by several other major newspapers, though framed in more cautionary language. Questions on the wisdom of such open association with the monarchy would be broached, as well as fears that the Entente powers might intervene should Germany seem to be slipping back into “old habits”. Within a week, the objectively insignificant matter of an ex-noble’s speech had been blown into a nation-wide debate on the nature of Monarchism and Germany’s future as a Republic.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck sat at the centre of this storm and became the focal point of the controversy which emerged, given his well-known monarchist background and open reverence for the German Empire. While only the most Left-wing papers attacked his character directly, a roundabout approach was taken by the pro-Republican forces which openly questioned “anti-Republican powers” in the government, demanding that all civil servants “openly and fully commit to upholding the German Constitution”. There was clear rhetoric drawn from the 1926 Referendum which had failed to fully purge monarchist influences from Germany, something which infuriated von Lettow-Vorbeck and many within the Reichstag, but nothing could be done without appearing more Reactionary than he already did. Public support remained in his favour, but a wrong move at this point could cost him much of the influence he had amassed in the last few years.

The duo of Otto Wels and Fritz Selbmann faced down President von Lettow-Vorbeck and Minister Kurt von Schleicher without an ounce of fear in their eyes, only the burning, unyielding sort of resistance which typified the SPD coalition. The air in the room was tense, all four men sitting with their backs ramrod-straight as if prepared to enter physical combat.

Otto Wels had been a leader within the SPD since the birth of the German Republic in 1918 and had become the face of their movement in Germany as a whole. He was a clever man with a sharp tongue and an inflexible backbone; he had once succeeded in convincing even Kaiser Wilhelm II’s most loyal troops to not oppose the new Republic and had only gone up from there. He was a man for whom one could not help but hold a measure of respect, though his radical political ideas prevented men such as von Lettow-Vorbeck from gaining anything beyond this measure.

Otto Wels

(https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_Wels#/media/File:Ottowelsportait.jpg)

Wels, as the most experienced politician present, did most of the talking. His voice was level, but firm. “We will not roll over and take this blatant trodding-upon of the German Constitution,” he warned the president.

“What do you mean?” Von Schleicher’s attempt to play innocent was ruined by his naturally-suspicious face. “A private citizen and close family friend spoke on behalf of said friend at a funeral, anything more is simply rumour peddled by subversives.”

“The same ‘subversives’ whom you hunted down in the streets like mad dogs?” Selbmann demanded, gripping the edge of the table and leaning forward. He bared his teeth as though in keeping with his metaphor. “You have crushed the people’s right to even be subversive! You and your pet monster, Göring.”

Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s expression did not change at the verbal attack, cold eyes remaining locked on the man. Selbmann was a former member of the German Communist Party, surviving the purge initiated by von Lettow-Vorbeck and finding a new home in the SPD. A clever, slippery man by his own definition, his introduction to the upper echelons of power within the SPD had been near-guaranteed as a way to help assimilate the orphan Communists once their more prominent party leaders had been jailed or fled the country. Selbmann was clever, blisteringly so, able to worm his way out of the anti-Communist crackdown and rise to become a leader within the SPD in just a few years.

Fritz Selbmann

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz..._0000571_002_Fritz_Selbmann_am_Rednerpult.jpg)

Wels did not attempt to hold back his teammate, just sitting back and waiting until Selbmann had sent the air circulating before he said, “We are not the fools your propaganda paints us as,

Herr Präsident. We see what you are trying to do; Germany will not become another Italy, slave to the fascist dog. Not while Prussia stands against you.”

President von Lettow-Vorbeck’s voice was low, almost a whisper as he said, “You are no Prussian.”

“Why?” Wels challenged. “Because I’m not a Conservative? Because I oppose the old order? You are as Prussian as I, yet I cannot imagine you willingly succumbing to the whims of a fluctuating monarch as in the days before Napoleon. Prussia was once the Conservative industrial heartland of old Europe; now, a century later, she is the democratic bastion of the Reich. I am Prussian because I believe in Prussia’s greatness and future, not through blind loyalty to her past.”

“Loyalty to Prussia should not come secondary to loyalty to the Reich,” said von Schleicher.

“Ironic, then, that your party is founded by the same men who pushed Prussia’s hegemony from 1871 until 1918,” Selbmann shot back, referencing Prussia’s eclipsing of the other federal states for the duration of the German Empire’s existence.

“Paul Löbe spoke of exporting Prussia’s so-called ‘successes’ to her neighbours. The SPD has long been an advocate of centralising; how is this so different from what Prussia has done?”

Wels shook his head. “Because you forget that Prussia is not Germany. A unified, centralised Germany is not one with Prussia’s boot on its neck, but one where Prussia is simply a part of a greater whole and these petty distinctions like ‘Bavarian’ or ‘Saxon’ become irrelevant. Should Germans not be loyal to Germany before their home regions? Recall how close we came to splintering in 1918?”

“You forget yourself,” von Lettow-Vorbeck hissed, leaning forward suddenly. “Good men fought the insurgencies. Died to defend our nation. Men like you two sat on the sidelines and watched.”

The two SPD representatives did not so much as flinch. “And once again the Reactionary lion rears his head,” Selbmann mocked.

“I served in the army. 1895 until 1897,” Wels corrected the president, meeting his gaze evenly. “Would it surprise you to learn that I left because of the treatment I faced for my politics, not from a lack of loyalty?”

Von Schleicher cut in before the situation dissolved. “What, precisely, do you desire from us?” he inquired, neatly folding his hands. “Reasonably,” he added a half-second later.

“The ban on the KPD must be lifted,” Selbmann demanded immediately. “It is a wholly undemocratic and unconstitutional encroachment on the rights of citizens.”

“We want you to hold a new federal election, a fair and legitimate one this time,” Wels chimed in. “This minority government you are running hedges dangerously close to a dictatorship.”

“You clearly lack crucial understanding of the concept if you believe that a dictator would allow you the leeway you already have,” the president dismissed. “Your demands are ludicrous and disproportional. What power do you have to enforce them?”

“We have the power of the people,” began Wels, but Selbmann cut in before he could finish.

“Germany needs Prussia. Prussia is the backbone of the Reich, the stabilising force holding it together. Germany needs Prussia, but Prussia doesn’t need Germany.”

The three other men stiffened at the implication. Von Lettow-Vorbeck jerked backwards as though he had been struck, though the other two gave Selbmann equally disbelieving looks. Wels recovered the quickest of the three, clearly favouring a united front approach by turning to the two opponents and nodding resolutely to communicate his agreement, extreme though he clearly found the threat.

On principle von Schleicher wanted to call troops into the room and see Selbmann thrown into a dark, cold cell on the Baltic Sea, but he forced himself to react rationally. The threat was genuine, he knew; extreme and nigh-unenforceable, but genuine. Secession. The last stage of a desperate and angry people. For a long time his goals had kept the threat of the Rhinelanders, the Bavarians, or the Silesians in the corner of his eye, but before now the notion of Prussia leaving Germany had never crossed his mind. It was ludicrous—unthinkable. As had been stated, Prussia was the backbone of Germany, its influence and territory woven through and around everyone and everything. Could there even be a Germany without Prussia? Von Schleicher did not know, and that uncertainty worried him deeply.

“You overestimate your influence,” said von Schleicher.

Wels barked out a laugh. “Are you truly so detached from the land you govern?” he asked, tone surprisingly bitter. “You attack political opponents, you unleash the

Reichspolizei against peaceful protesters, you flagrantly oppose the norms and values of the Republic which so many fought for… are you so deaf to all but your own ego that you disregard the voices which oppose you? For there are many, I assure you.”

Von Schleicher glanced at von Lettow-Vorbeck. The president had not lost the stone-like expression, but in his eyes there was just the smallest hint of… what, exactly? Surely not uncertainty, but von Schleicher could find no better word. “I, too, have had the support of the people, lest you forget,” the president at last spoke up, voice carefully level, “and I will not let the people’s trust in me be pushed aside by the likes of you.”

“Then accept our deal,” Wels insisted. “Show the people that you are willing to compromise, to admit your own wrongs. Hold new elections and call a new election on the expropriation of royal properties—”

“No,” von Lettow-Vorbeck all but growled, holding up a hand. “That I will not do. I have already allowed your lot far greater leniency than my good sense and conscience find acceptable. Even more than your gall, I find the sheer hypocrisy of your demands appalling. You dare to criticise my so-called ‘attacks’ of political opponents while trying to blackmail me into doing the same towards those whose politics you dislike.” He shook his head, lip curling. “You disgust me. We are done here.”

Von Schleicher said nothing despite his personal reservations, waiting until the duo had departed—Wels silently, Selbmann with a lingering sneer—before he voiced his concerns to the president. “I am unsure if that idea was wise,” he began.

“Their concessions were excessive and they knew it. I am not the Reactionary dictator as which they wish to portray me. I have granted them many allowances in the Reichstag; too many, many have already said. They have no right to come to me and demand more.”

“They will use this to try and discredit your Republicanism.”

“When have I ever sought to portray myself as a friend to the Republic?” This was said in a somewhat joking manner, though von Lettow-Vorbeck continued quickly with, “My respect for the imperial family is easily-construed as a matter of wartime camaraderie, no?”

“I will have to speak with Göring on the matter, he has been dealing with much of the public backlash on the matter and has a more authentic view of public opinion. Regardless…” The Minister of Defence hesitated, his next words feeling traitorous. “It might be in your best interests to publicly diminish your loyalties to the Kaiserreich, at least for now.”

Von Lettow-Vorbeck did not seem pleased at the proposition, but neither was he angry. “I will not denounce my principles,” he warned.

“No, nothing like that. A public statement of support for the German Republic and a denouncement of those who oppose liberty would suffice. Perhaps removing the imperial flag from circulation once more. The majority of papers have avoided targeting you with rumours and this would incite them to direct their focus elsewhere. It could even work to your advantage and let you turn it against some of your enemies.” He avoided naming names, as von Lettow-Vorbeck’s enemies were not necessarily von Schleicher’s.

“It could obstruct our future goals,” von Lettow-Vorbeck pointed out. “The seeds we have sown will come to naught if we cannot win the loyalty of the people. If we tip our hand too far in the direction of the Republic, it will become impossible to reverse.”

“I do not foresee that becoming a problem. You hold the loyalty of the military.”

“The military was loyal to the Empire and it fell despite this,” the old general again countered. “I do not wish to see a Germany where terror chokes the lives out of her people, but one where they can thrive under the protection of a powerful state. We are not fascists, after all. No.” He shook his head. “I will change nothing. Let them weave whatever rumours about me they like. The time for grand concessions is over. They will fall in line or they will be dealt with.”

Von Schleicher drummed his fingers against the table, considering the future. Their plans for Germany had been discussed at length and Prince Wilhelm was to play a crucial role in what was to come, both for their Fatherland and for Europe at large. The SPD was the biggest domestic obstacle towards their final goal: The restoration of the von Hohenzollern monarchy at the head of a reborn German Empire. If they were to succeed, their two biggest obstacles—the SPD within Germany and the Entente powers without—would have to be aligned or neutralised, and only then could this brittle, failed Republic fall and the German Reich be restored to its rightful place as the greatest of nations. Only time would tell if their efforts would bear fruit, or if von Lettow-Vorbeck’s reign would be seen as the last breath of a dying world order doomed to be erased.

(1) In contrast with real life, where Hitler built him a memorial at Tannenberg and buried him there in opposition to von Hindenburg’s will.