8mm to the Left: A World Without Hitler

"An empire is a terrible burden to bear. That kind of power, of majesty, it represents the ultimate pinnacle of human achievement, of transforming yourself and your land into a shining beacon on a hill. The burden is not the empire; it is the terror of wondering which tiny straw will bring the whole thing crashing down around you." - King Edward VIII, 1936

The Habsburg Realm

March 15th, 1933 was the date of demise for the first and only Austrian Republic. Following electoral irregularities, Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss used the Vienna Police to indefinitely postpone the reconvention of the Austrian Parliament, from then on ruling by decree. Though the country's constitution would not be changed to enshrine these changes until 1934, completing Austria's transition into an Authoritarian Fascist state, March 15 remains into the modern era a day of remembrance for the Austrian Republic.

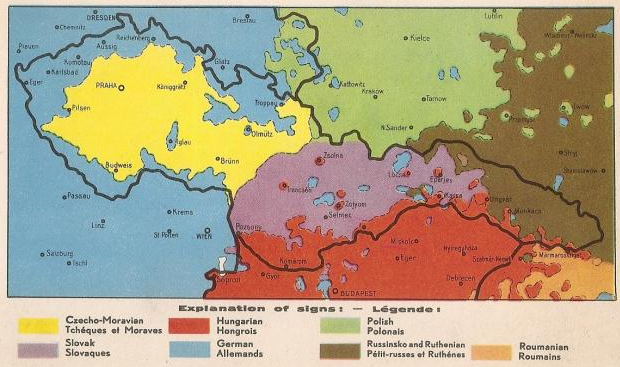

The Austrian Republic, like so many of its neighbours, was a product of the Great War, the last remnants of the collapsing Austro-Hungarian Empire which reformed itself into a democratic state. Initially calling itself the “Republic of German-Austria”, politicians in Vienna held out hope in Wilsonian claims to self-determination which might allow the new, purely-German state to achieve union with its German brethren. These hopes were not to be, and German-Austria would be stripped of its claims in Czechoslovakia and banned from ever unifying with their kin to the north.

Lands claimed by the Republic of German-Austria

(https://www.deviantart.com/wolfgrid/art/Republic-of-German-Austria-683595245)

To say that the Austrian people were angry at this treatment would be an understatement. Not only had their historic empire been ripped away and their country marred by a lost war, more than 4 million Austrian Germans (mostly in the Sudetenland but also living in communities across what was now Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Romanian Transylvania) were now citizens of foreign nations. This did not even touch on the economic devastation that this dealt to Austria; prior to the war the majority of Austria’s food had come from Galicia-Lodomeria (now in Poland) and Croatia (now in Yugoslavia). Of the territory which remained within this new rump Austria only 17% was arable, meaning that Vienna would be forced to import large quantities of food. At one point in the early 1920’s these ex-subjects imposed a trade blockade on Austria which may have led to a true famine had the Entente members not intervened to prevent the utter collapse of the state. Few believed that Austria could be economically and politically viable without being part of a greater whole and support for

Anschluss (union) with Germany skyrocketed.

Austria (blue) alongside its former territories

(https://www.discusmedia.com/maps/austria_region_maps/3735/)

This question of an Austria separate from Germany came to dominate politics in the 1920’s. A leading opponent of the idea of joining a “Greater Germany” was the Christian Social Party, a Conservative and Catholic-dominated organisation which opposed

Anschluss on primarily religious grounds, seeing Germany as too Protestant and fearing Austria’s cultural decay if allowed to join. Germany’s economic woes throughout this decade aided their narrative but despite this the party was unable to make a significant dent in the pro-German faction, as Austria was little better. It did not take long for the question of

Anschluss to become a political rift, with Democratic and Liberal factions favouring union while Conservative and religious ones opposed it.

Given all of these trials and tribulations, it is perhaps surprising that the Austrian Republic lasted as long as it did. Chancellor Dollfuss’s so-called “self-coup” of Austria would be seen as little more than a last-ditch attempt to save what was seen as a non-functioning state.

The collapse of democracy in Austria was met with mixed reactions within Germany, largely dependent upon the political affiliation of the given individual. As one might expect, the SPD and the various other republican parties mourned; the Zentrum were hesitantly curious, admiring the staunchly Catholic policies of Dollfuss; the DNVP and their various far-Right allies were infuriated. Nearly all breadths of the political spectrum viewed Austro-German unification as natural and the biggest question regarding Authoritarian Austria was where Germany fit into their plans. The answer? Nowhere.

Engelbert Dollfuss was, first and foremost, an Austrian nationalist. Back during the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire he had opposed the push towards federalism and now he opposed Austria becoming in any way subordinate to Germany and, in his mind, Prussia. The Archduchy of Austria had been old when the Kingdom of Prussia had been birthed into the world and the notion of ancient, grand Vienna, a city on par with Paris and London, becoming lesser than Berlin made the very notion of

Anschluss anathema to him.

Instead Dollfuss would begin drawing closer to Austria's former partner, Hungary, as well as their ideological brother to the South, Italy. All three nations shared certain core tenets, even if the exact expression of their ideologies varied by nation. These tenets included the primacy of the Catholic faith, the opposition to Communism, and the belief that only a strong, undemocratic leader could secure the culture and ideals of a nation. Interestingly, it was Portugal whose ideology Austria's would appear most similar to rather than Italy, in particular the corporatism which had defined the Estado Novo in Portugal. A unifying element of Austrofascism would come to be the former Habsburg monarchy, and the belief that the former ruling imperial family had been of the rare breed of rulers with a true "Divine right to rule", epitomised by their close bond to the Holy See. This was contrasted with the supposedly "atheistic" von Hohenzollern family, rulers who had the audacity to break from Catholicism and even to crown themselves at their coronations.(1)

Otto von Habsburg, claimant to the now-defunct Austrian and Hungarian thrones, would come to have an increasing presence in this new Austria, especially after 1934 when Dollfuss repealed the Habsburg Laws which had banned the former ruling family and confiscated their property, allowing him to return. Though the idea of a full monarchic restoration was put on a back-burner due to fears of intervention by the neighbouring anti-Habsburg states, interest in the ex-royals remained potent.

Otto von Habsburg

(https://www.economist.com/obituary/2011/07/14/otto-von-habsburg)

Dollfuss's brand of Authoritarianism, retroactively named "Austrofascism", brought Vienna firmly into the camp of Italy. While Austrian nationalists rankled at siding with the traitorous old foe of Italy (which hadn't existed even as a dream when their grandfathers were young, they often reminded each other), and looked covetously across the Alps to German-speaking South Tyrol, they were nevertheless forced to swallow their pride and accept the status quo. Italy was far too powerful to oppose and this sacrifice was seen by many as a price to avoid the far greater sacrifice which was absorption into the Protestant-dominated Germany. Dollfuss was keenly aware of the popular support for

Anschluss within both Germany and Austria and would tackle this issue head-on. In exchange for abrogating claims on the southern half of Tyrol, Mussolini guaranteed the independence of Austria against any potential German aggression. As a sign of further goodwill, Italy would begin providing financial support for the struggling Austrian economy, support which Dollfuss claimed credit for as a way to boost domestic popularity.

Despite all of this, Dollfuss and his party

Die Vaterländische Front (The Fatherland Front) would struggle to win over many elements of the Austrian population. The former republic had possessed a not-inconsiderable loyalist Liberal element and, aside from the Church, the bureaucracy, and the most isolated peasantry, people craved representation. An unfortunate side-effect of this was a greater longing for union with the German Republic during his rule than prior to it, in particular in the western regions of Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and Salzburg, whose economies and cultures were already more intertwined with that of neighbouring Bavaria than the East and South of the nation. Many also saw his attempts to curry favours with Italy as a sign of humiliation and opposed him on that alone. Dollfuss would be forced to commit a portion of his funds to suppressing dissent in these regions and it would result in a further drain on the already thinly-stretched budget.

The success or failure of Dollfuss's regime is still debated by contemporary historians. On the one hand, his regime succeeded where other Authoritarian strains failed, acquiring complete power over the state and succeeding in his main goal of ensuring Austrian independence from Germany. On the other hand, Dollfuss's policies would fail to jump-start the struggling Austrian economy and his single-minded focus on preventing German hegemony would play an enormous factor in turning Austria into what many consider to have been a puppet state of Mussolini's Italy. By the end of 1934, the Federal State of Austria would be reduced into a mere cog in Mussolini's grand design for Europe and, if he succeeded, the world.

The nation of Czechoslovakia was a young one by European standards, younger by far than all of its neighbours. The result of years of lobbying by Czech and Slovak politicians to the powers of the Entente during the Great War, the two peoples had at long last achieved unity and independence from Austria and Hungary via the Treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Trianon in 1919 and 1920, respectively. After centuries of cultural and linguistic oppression by the Austrians and Hungarians, this kind of union was a dream come true; however, it would not come without its own difficulties.

The first and arguably greatest hurdle was of the ethnic variety. The borders claimed by the Czechoslovak politicians were ambitious to say the least and coincided more with geographically-defensible borders than ethno-linguistic ones. In the East, the Slovak half laid claim to the majority of the mountainous Upper Hungary, taking with it a sizeable chunk of Hungarians (almost 800,000) and Ruthenians (500,000), not to mention thousands of Poles and Germans in various pockets. In the West, the Czech half had fewer minorities (only Poles and Germans), but simultaneously the most troublesome of these: The Sudeten Germans.

The Western regions of Czechoslovakia were comprised of the regions of Bohemia and Moravia, formerly the independent Duchy and later Kingdom of Bohemia during the era of the Holy Roman Empire. The reign of the Bohemian kings had seen waves of immigration from across the rest of the Empire, mainly craftsmen and merchants but also a significant number of students who came to attend the Charles University in Prague. The rulers had promoted this immigration as it brought many skilled workers and had helped develop Bohemia into one of the richest regions of Central Europe. Following Bohemia and Moravia's absorption into the Habsburg Monarchy during the 1600's this slide towards Germanisation only grew, with German becoming the dominant cultural and bureaucratic language in accordance with the capital in Vienna. Though the hinterlands retained their Czech culture, most major cities, as well as the mountainous Sudetes border regions, were mostly or completely German-speaking by the 20th century.

Ethnic map of Czechoslovakia

(https://mapsontheweb.zoom-maps.com/post/621613495243456512/ethnic-groups-in-czechoslovakia-hungarian)

It was the fall of Austria-Hungary and Bohemia and Moravia's—collectively referred to as Czechia's—separation from the rest of Austria which brought this ethnic question into the forefront of discussion. The historical border of Bohemia had long followed the defensible mountains encircling the region and it was both strategy as well as historic precedent which was cited in defining Czechoslovakia's new Western border. Austria likewise laid claim to this region as part of the new "Republic of German-Austria" in 1918 but was unable to win over the Entente, who saw a strong Czechoslovakia as the greatest assurance against Austrian, Hungarian, and especially German dominance over the region. Consequently the so-called "Sudetenland" border region would be enfolded into Czechoslovakia and 3.1 million Germans with it. It would quickly prove itself to be one of the most valuable regions in Czechoslovakia, containing the majority of the nation's industry, and dependence on Sudeten production would further push the government to keep hold of the region.

3.1 million people was far more than a mere minority, but in truth a plurality. Though less than the 6.5 million Czechs in Czechia, they significantly outnumbered the 2.2 million Slovaks, further frustrating the Sudeten Germans who felt themselves to be invisible despite outnumbering one of the two founding peoples. The government in Prague would attempt to resolve this by removing much of the dialogue referring to "Czechs'' and "Slovaks" and replacing it with "Czechoslovaks", claiming the state as one nation and people seperated by circumstance rather than real difference. Compared to 8.7 million Czechoslovaks, 3.1 million Germans suddenly seemed less daunting, but the cracks begin to show early. Many saw this as an attempt to refuse Slovak autonomy (which would have then been demanded by the Sudeten Germans) and referred to the policy as "Czechisation'', and they were not entirely unjustified in doing so. Aside from the capital and majority of the industry being located in the Czech half, Czechs were also overrepresented in politics and administration, with the prevailing language for postal, railway, and army institutions being mostly or only Czech. Whether or not this was part of an active policy of Slovak suppression is debated, and most experts concur that it was not malicious. The simple truth was that Czechia possessed a far greater pool of skilled workers and businesses to pull from than the Slovakians, just as the Austrian Empire had had in comparison to the largely-agricultural Kingdom of Hungary.

The instability and financial crisis which wracked Germany during the early 1920's had put a lid on the situation for the time being (Czechoslovakia being a far more stable option at that point) and allowed Prague to turn their focus elsewhere. The Germans were not the only troublesome minority, and soon Czechoslovakia and Poland would be butting heads over another strategic region: Teschen Silesia.

Disputed Czecho-Polish Teschen

(https://english.radio.cz/czechoslov...19-a-brief-clash-lasting-consequences-8139977)

Teschen Silesia, formerly Austrian Silesia, was a region in North-East Czechia bordering Poland which both of the new republics claimed as their own. For the Czechs, the claim was historical and strategic: Beyond its centuries-old place within the Czech state, it also held the vital railway connecting the region to Slovakia, not to mention a veritable treasure trove of coal mines and ore. For the Poles, the claim was ethnic and economic: The most recent Austrian census defined the region as majority-Polish and control over it would help grow their industrial independence from a resurgent Germany or Russia.

The dispute over Teschen grew into a conflict and finally a series of invasions and counter-invasions which only ended when the League of Nations intervened and determined the new border granting a majority of the region to the Czechs and creating a sizable Polish minority in Czechia. The dispute over this region would result in Polish exclusion from the so-called "Little Entente", the Czech-led alliance of states seeking to preserve the new status quo and prevent Austrian and Hungarian revanchism, as well as an overall anti-Czech sentiment in Warsaw as many awaited the chance to reclaim Teschen and perhaps a bit more.

The Hungarians in Southern Slovakia may have been fewer than the Germans but they were nearly as frustrating for the government in Prague. The difference between the Germans and the Hungarians was that the Germans controlled the majority of Czech industry while the Hungarians did not. Slovakia was overwhelmingly underdeveloped (though still the most industrialised part of the former Kingdom of Hungary) and Catholic when contrasted to modern, mostly-secular Czechia and therein the Hungarians were differentiated only by their language. It was hoped by Prague that elevating the Slovakian half to the quality of life of Czechia would pacify the Hungarians, but the Great Depression—which took a particularly hard toll on the agricultural regions in the East—interrupted their goals.

In fact the effects of the Great Depression on Czechoslovakia would be among the worst in Europe, though not necessarily for economic reasons. Unemployment and financial woes would be most extreme in the industrial Sudetenland and the agricultural Slovakia, both of whom were hit hard by rising tariffs and cost of living. Though the negative effects on regions like the Sudetenland, Teschen, and Southern Slovakia were little different from those in neighbouring Germany, Austria, Poland, or Hungary, many in the beleaguered regions would feel that, if they must suffer, they might as well do so among their real countryfolk. Still others would outright deny the Depression as being an all-encompassing affair and rumours of the central government offloading the strain onto the minority regions (in some retellings including Slovakia as well) in order to prop up Czechia would spread like wildfire among the less-educated, their own version of the

Dolchstoßlegende (Stab-in-the-Back Myth).

Despite all of these setbacks and struggles, the beginning of 1935 would see a general optimism returning to the nation. The effects of the Great Depression were well underway to being undone and the staggering unemployment was returning to normal levels. A divide remained between the Czechs and the rest of the nation but even that was becoming less apparent as the first generation of truly Czechoslovakian students neared graduation and all hoped that the next generation would not even know the difference between a "Czech" and a "Slovak".

"Yugoslavia" is a word derived from the term "South Slavs", because that is how the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was envisioned: A union of the South Slavic peoples, from the Slovenes in the North-West to the Croats and Serbs in the Centre to the Bulgarians in the East. Of course, dreams are not always reflective of reality, and the Yugoslavia which emerged from the Great War was not the one which had been first dreamed up by South Slavic intellectuals during the reign of the Austrian and later Austro-Hungarian Empire.

For their participation in the Great War Serbia had always expected to make significant gains, claiming the Vojvodina from Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina from Austria, and several other smaller border regions which altogether would almost double the size of the state. It was not until the later stages of the war that a new dream would come to them and they would begin making plans to form not just a Greater Serbia, but a Serbian-led Yugoslavia. This plan was met with enthusiasm from France and America and, much like Czechoslovakia, the new union would be borne from the ashes of the Treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Trianon.

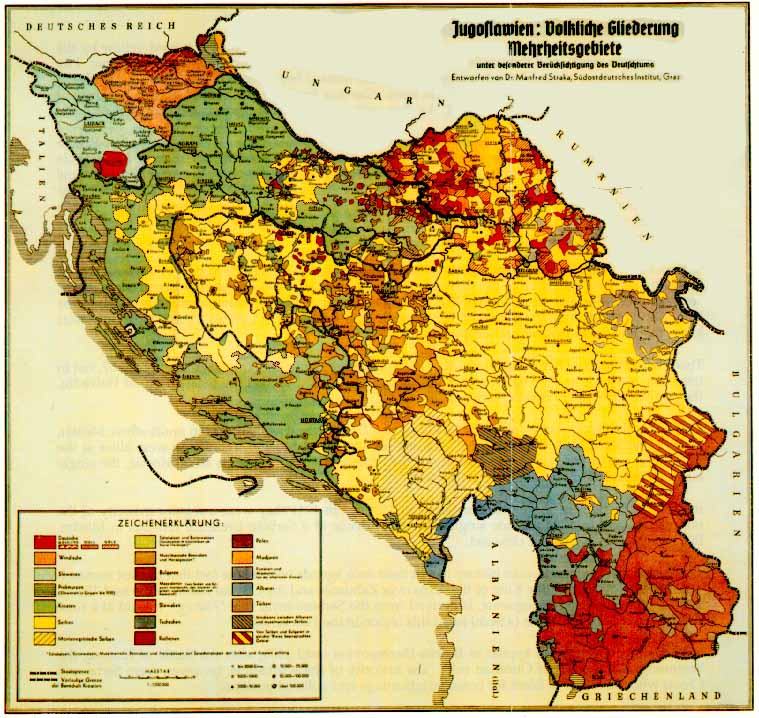

Yugoslavia in its inception was generally understood to be a sum of three parts: Slovenia (the northernmost and smallest), Croatia (centrally-located and encompassing historical Slavonia and the Adriatic coastline), and Serbia (the largest and dominant of the three reaching from Hungary down to Greece). Likewise, citizens of the nation were expected to fall into one of these three subgroups. In practice, it was not this easy, as many of the lands now encompassed by Yugoslavia included either minorities from the lands they had been taken from or others who considered themselves different from the above groups for one reason or another. Slovenia had Germans located along the northern border and in the Gottschee region; Croatia had pockets of Italians along the Dalmatian coast; Serbia had Hungarians to the North, Albanians in the Centre, Muslim Bosnians to the West, and Bulgarian Macedonians to the South. The last two were an especially touchy topic for Belgrade because both were considered South Slavs and yet their place in the new state was uncertain; Bosnians were ethnic South Slavs who had converted to Islam under Ottoman rule while Macedonians considered themselves a subgroup of the Bulgarians and actively sought unity with Sofia at every turn. Neither was a group which the central government considered trustworthy yet neither were different enough to try and expel or oppress.

Ethnic map of Yugoslavia c. 1930

(https://www.srpska-mreza.com/library/facts/map-Nazi-1940.html)

In some ways the formation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from the Kingdom of Serbia mirrored the formation of the German Empire from the Kingdom of Prussia, with the king of a solitary state being elevated to the ruler of a broader cultural union. The first king of Yugoslavia was Alexander I and his policies would seek to deal with the cultural divides splitting the young nation from its inception. Alexander and his government used the very real fear of Italian, German, Hungarian, and Bulgarian invasion to unite a disparate people into a functioning whole by attempting to form a "Yugoslav" identity as a counter to the more powerful regional ones. The historic regions were abolished in favour of new internal boundaries based on geographic features and named for the rivers as a way to undermine separatism. Federalism was traded for centralism. Religious and linguistic variance, while not forbidden, was increasingly curtailed in favour of forging a united front from a disparate group. It was a noble goal, but its greatest hurdle was Alexander's choices of template. In almost all things, Serbian was used as the baseline for what defined a "Yugoslav". Latin-based spelling in Croatia and Slovenia was replaced with Cyrillic, greater political representation went to Serbs even in non-Serb regions, and authority was gradually sapped from the cultural capitals of Zagreb and Ljubljana in favour of Belgrade.

These pushes towards Yugoslavism—or, more accurately, Serbianism—did not sit well with the non-Serbians, especially the Croats and Slovenes, many of whom felt that they had simply traded in an apathetic but at least Catholic emperor in favour of a malevolent Orthodox king. These feelings were emulated by the Macedonians, Hungarians, and Albanians, all of whom received funding and support from the nations which claimed them in hopes of triggering a collapse of the Yugoslav government.

Italy would prove to be the largest threat to Yugoslav independence. Italy had long laid claim to the coastal region of Dalmatia and had double-crossed their allies Austria-Hungary and Germany in hopes of gaining this boon. However, at the last moment it had been snatched from their maw by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his desire for self-determination, ceding the territory in its entirety to Croatia and in turn Yugoslavia. This had not deterred the Italians, and barely had the Great War ended than they had strong-armed the Yugoslavs into ceding the port cities of Zara and, later, Fiume. These two cities had not quenched Rome's thirst and as the years rolled on, hungry eyes would covet the rich fields of Dalmatia as a destination for settlement, regardless of the peoples living there who very much did not identify as Italians.

Fiume (North) and Zara (South)

Anti-Italian paranoia would curb much of the Croatian and Slovenian secessionist tendencies throughout the 1920's as the two understood that breaking away from Yugoslavia would immediately result in Italian invasion and occupation. Further reassurance came with the increasing ties with Romania and Czechoslovakia, but the protection of a Great Power was still felt mandatory. Despite historic Serbo-Russian bonds the USSR was considered a non-option for Alexander and the rest of the government's virulent loathing of Communism (and in fact Yugoslavia would refuse to recognise the Soviet Union as legitimate throughout this period). France was the most desired ally as a nation bordering Italy and primed to invade should it come to the worst, and much of Alexander's foreign policy would be based around ensuring French support and protection. This would culminate in his trip to Marseilles in 1934 in hopes of securing a true alliance, where tragedy would strike before his goal would come to pass.

The assassination of King Alexander I in Marseilles was a tragedy for his Serbian subjects and a ray of hope for many of the rest. It had been carried out by Vlado Chernozemski, a Bulgarian and member of the IMRO, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation, a terrorist group working to separate Macedonia from Yugoslavia and unify with Bulgaria. Yugoslav politicians would be quick to point the blame at Mussolini for his support for the various separatist organisations including the IMRO and

Ustaše, a group of Croatian terrorists working to achieve independence from Yugoslavia. Many of the

Ustaše, including their leader, Ante Pavelić, had been hiding out in Italy thanks to asylum granted by Mussolini, and it did not take long for him to come under suspicion of involvement in the assassination of the king.

It was through the machinations (both real and coincidental) of Mussolini and Pavelić that the Franco-Yugoslav Alliance would fizzle out before ever coming into existence. France had been increasingly looking to Italy as a potential ally against a possibly-resurgent Germany and was therefore reluctant to offend them. Pledging protection to Belgrade was one thing; supporting them in an accusation against

Il Duce himself was quite another. When Mussolini refused to hand over Pavelić, France was forced to choose a side, and Yugoslavia came out the loser.

Franco-Yugoslav relations cooled rapidly after this affair and Belgrade increasingly looked towards its more immediate neighbours for protection, including Romania and Czechoslovakia. Unfortunately, both of them were increasingly prioritising their own Great Power threats—the Soviets for Romania and Germany for Czechoslovakia—and retained their trust in France, something which could not be said for Yugoslavia anymore.

With the death of King Alexander, the throne fell to his son, Crown Prince Peter, now King Peter I of Yugoslavia, at the time only eleven years old. Due to King Peter’s youth a regency was established with his cousin, Prince Paul, as caretaker of the throne until Peter came of age in 1941. It was with a heavy heart that Paul did this and the regency would pull him between two extremes; on one end, Paul had never supported the Serbo-centric viewpoint of his cousin nor Alexander’s penchant for unchecked monarchism, and believed strongly in democracy and federalism as the road to a united Yugoslavia; on the other end, his moral principles dictated that the kingdom be handed over to Peter unchanged to do with as he saw fit, thereby forbidding Paul from making any of the changes he envisioned. In this sense he was the perfect regent, but an imperfect ruler.

Yugoslavia would enter 1935 far more fragile than it had been just a year before. A child king and his regent on the throne, increasingly-rebellious minorities, and greedy neighbours in all directions, it had become clear to all that the peaceful days were behind them and only storms lay ahead.

(1) The Prussian monarchy actually did make a habit of crowning themselves rather than having a bishop do it.

Author's Note: This chapter is mostly a filling-in on the status of the Western Balkans and does not break much new ground; however, it does show some small butterflies which will become relevant later.