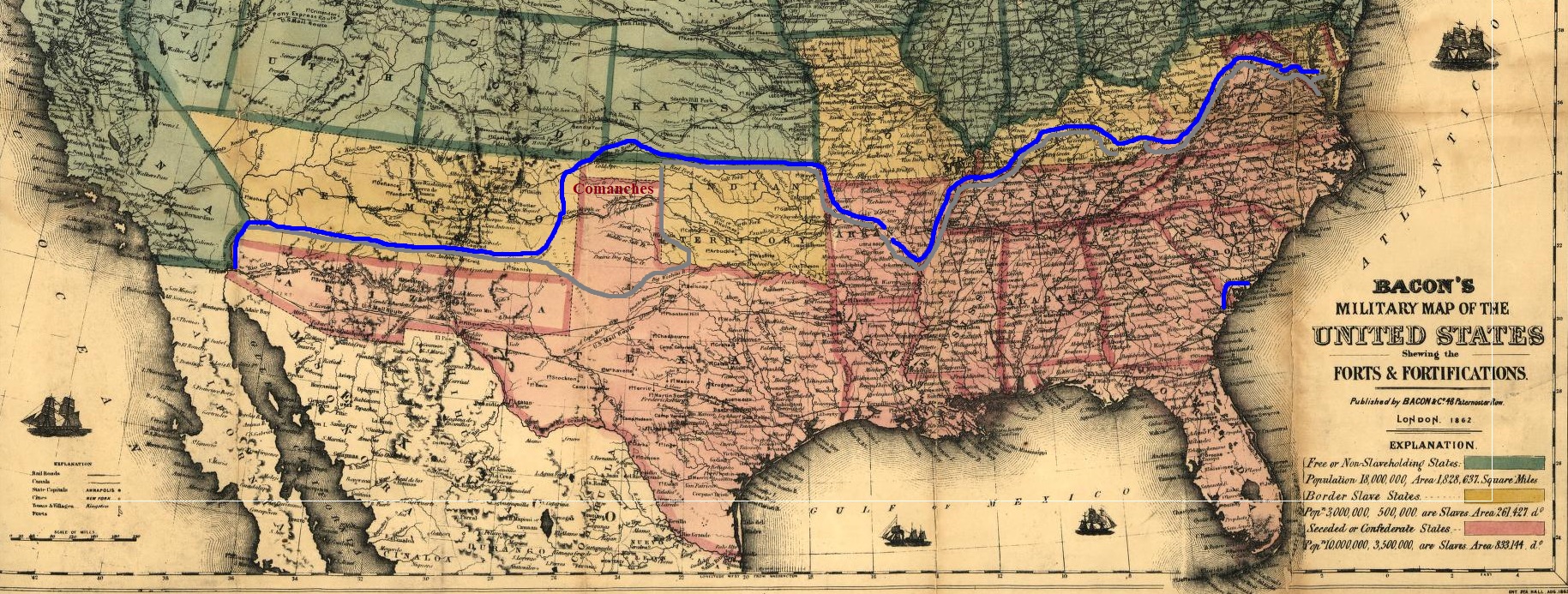

To encapsulate, in the West, the stalemate in Arizona continues, while the Comanche are effectively driving the settlers out of swathes of territory and cutting the Santa Fe trail, with no troops to deal with them. The Indian Territory is in Confederate hands for similar reasons. Meanwhile, the Union is in control of Arkansas north of the Arkansas River, while having fortified posts along the shores of the Mississippi, but as we can see are not close to cutting it. The main strength of the Union in the West is fighting in northern Tennessee and central Kentucky. Bragg's efforts to unleash Kirby Smith has put the Confederacy once again back in Bowling Green, as the defeat outside of Knoxville has forced Grant back to find winter quarters for his troops, but also draw off men to try and boot Kirby Smith out.

East into Virginia, the Union controls West Virginia, while the lines have mostly stabilized between the Rappahannock and Centreville for the Union and the Confederacy. Meanwhile, Farragut's expedition controls Port Royal and Beaufort in South Carolina, establishing ground for the (hopefully) new blockade of the Confederacy in 1865. Militarily, this is where things stand at the end of 1864.

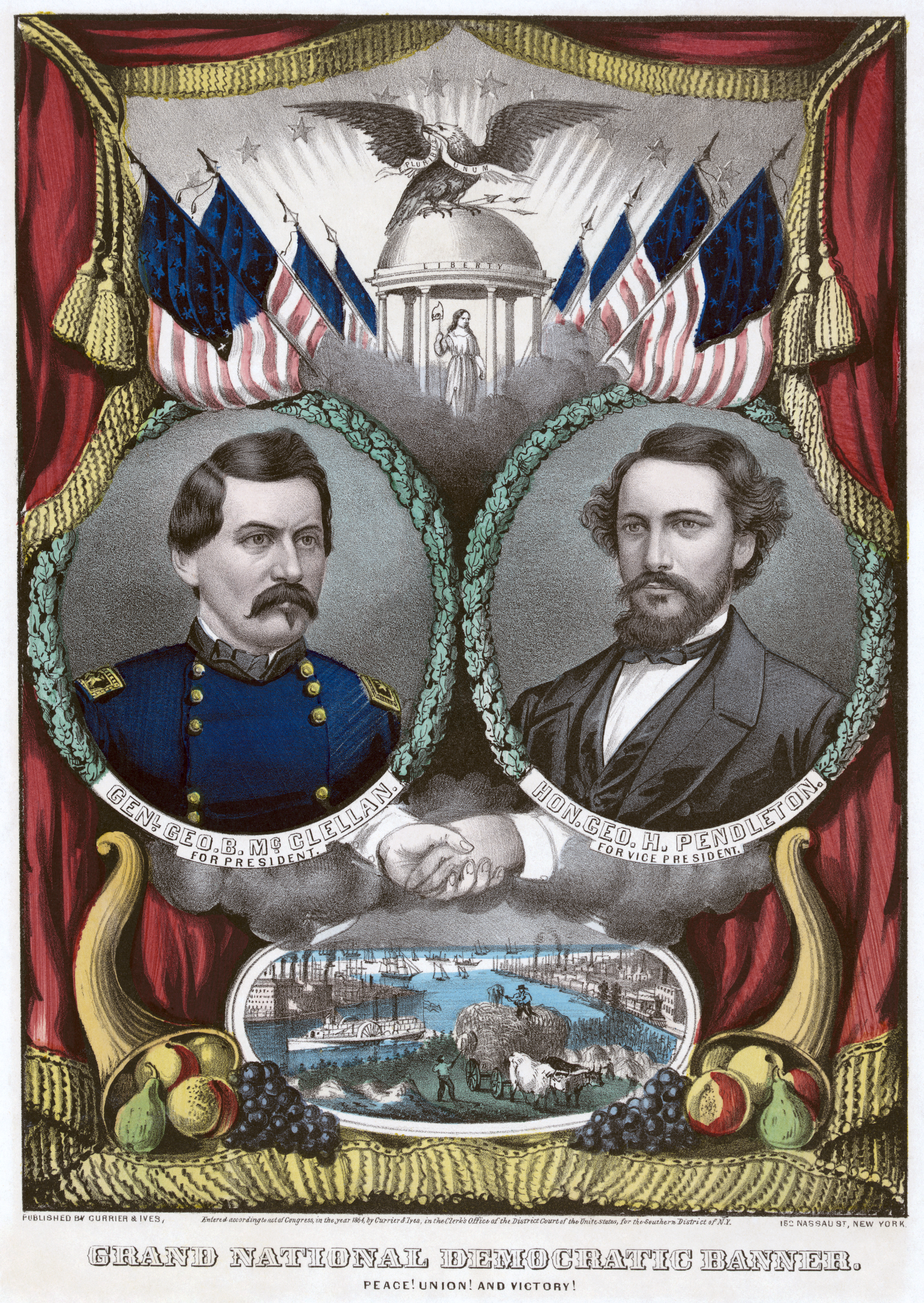

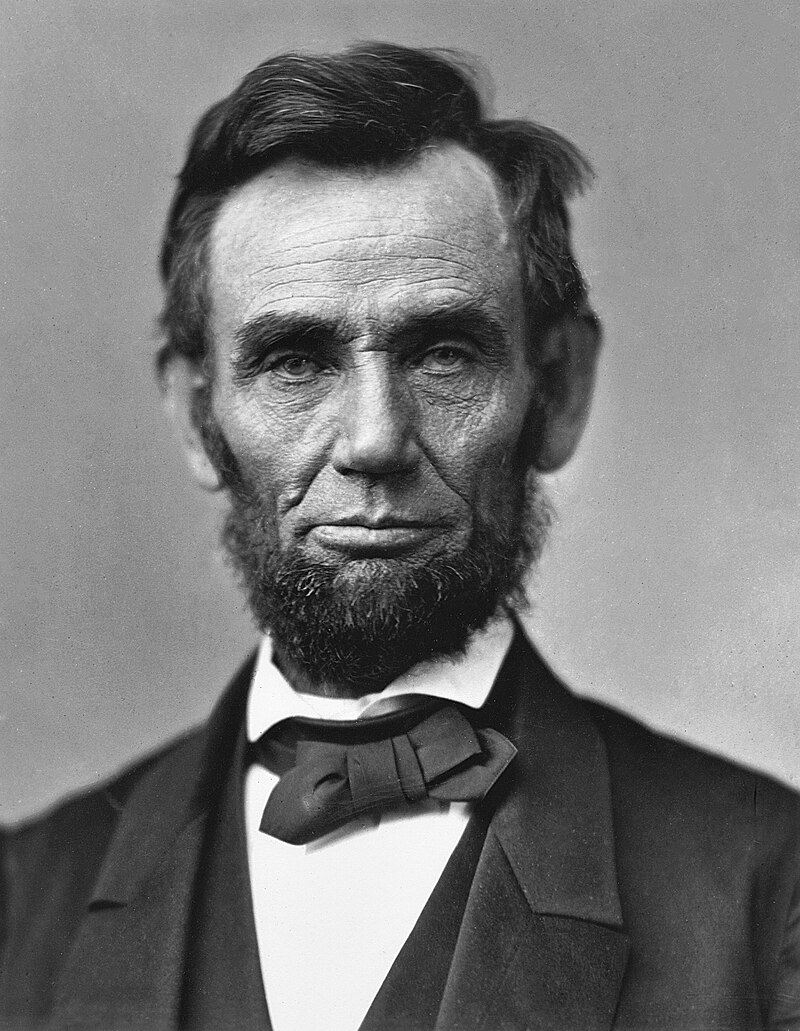

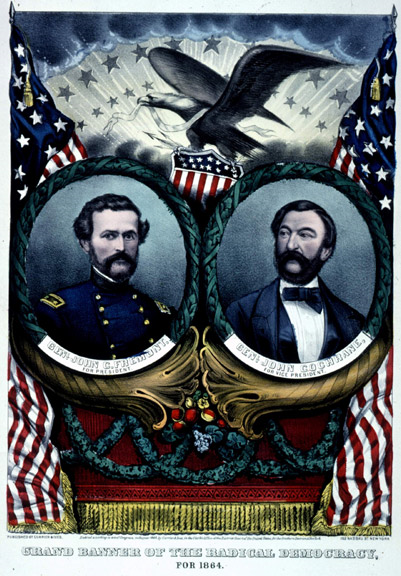

And thank you to Bacon's Military Map of the United States, here are the lines for the front come November 1864 as I work furiously away at the election!