“It is not uncommon, in many retellings of the American Civil War, to cast Gen. Lee in the same spotlight as Gen. Washington or Gen. Bonaparte. Certainly, Gen. Lee’s long, storied record of military service, tracing back to the days of the Mexican War, is an impressive résumé. His victories in Matanzas and Habana, Norristown and Havre de Grace, are lauded as astounding tactical triumphs, and are still taught in West Point classes to this day. It is true that Gen. Lee had many victories in his day, but what often are unattributed to his legacy are his equally numerous failures on the battlefield. They call Gen. Grant a butcher, but was it he who threw thirty thousand corpses at the guns of Philadelphia? They say Gen. Sherman was a tyrant, but was it he who could not overcome the muskets and bayonets of Appalachian miners and Southron chainbreakers?

Gen. Lee was a man of great military achievement, but the ranks of any war machine are stocked full with such men. Instead, one must ask, why did a general who holds a reputation as highly regarded as Caesar or Alexander

lose so much?”

- John Watts de Peyster, Memories of an American War

(New York; Harper & Brothers, 1875), p. 36

Shannon Avenue

Lecompton, Kansas Territory

May 1, 1860

Though it was the dead of night, the tongues of flame that consumed Capitol Square cast such a strong, warm glow over a city of fresh timber and tar that one would be forgiven for thinking the sun had begun its rise a few hours earlier than usual. Fire had blown out the windows of the unfinished Territorial Capital Building, and it had leapt across the street to begin its ravenous consumption of the rest of the city. People stirred in their beds, waking to nightmares and quickly grabbing their spouses, their children, and what few belongings they could manage before taking to the streets in flight.

Twelve hours before, at high noon, Lecompton had been celebrating; the eponymous state constitution had been signed in the building that now burned, bringing Kansas into the Union as the thirty-fourth state, and the eighteenth slave state. As the ink dried, the abolitionist John Brown sat rotting in a makeshift prison on the open-ceilinged second floor, exposed to the elements with nothing more than a threadbare blanket to warm himself. Ignoring the triumphant jeers of the men who guarded him, John Brown kept his eyes closed and his hands clasped together, mumbling his prayers to the Christian God. His execution was scheduled for the following morning at dawn, on slaver soil.

Twelve hours later, at midnight, as Lecompton was ablaze, John Brown was no longer jailed. Instead, he walked on slaver soil between burning buildings, a rifle back in his hands, following James H. Lane and his band of abolitionist Jayhawkers out of the city, meeting any opposition with the hellfire of bullets.

Years ago, when Kansas had first begun bleeding, this group of men had been branded radicals. Tomorrow, they would be lauded as heroes in newspapers in San Francisco, in Chicago, in Philadelphia, in Boston.

The Jayhawker Brigade rode out of the city, heading east along the curving riverbank. Hours later, Lawrence emerged on the horizon, its low buildings standing tall against the flat grasslands. The men who stood at the roadside with Springfield rifles in their arms let out a great cheer when they saw John Brown’s bright blue eyes pierce the night, his wild white beard like a shock of lightning against the sky.

As dawn began to break, whispers rolled over Lawrence like stormclouds: “

The Mad Prophet has been freed.”

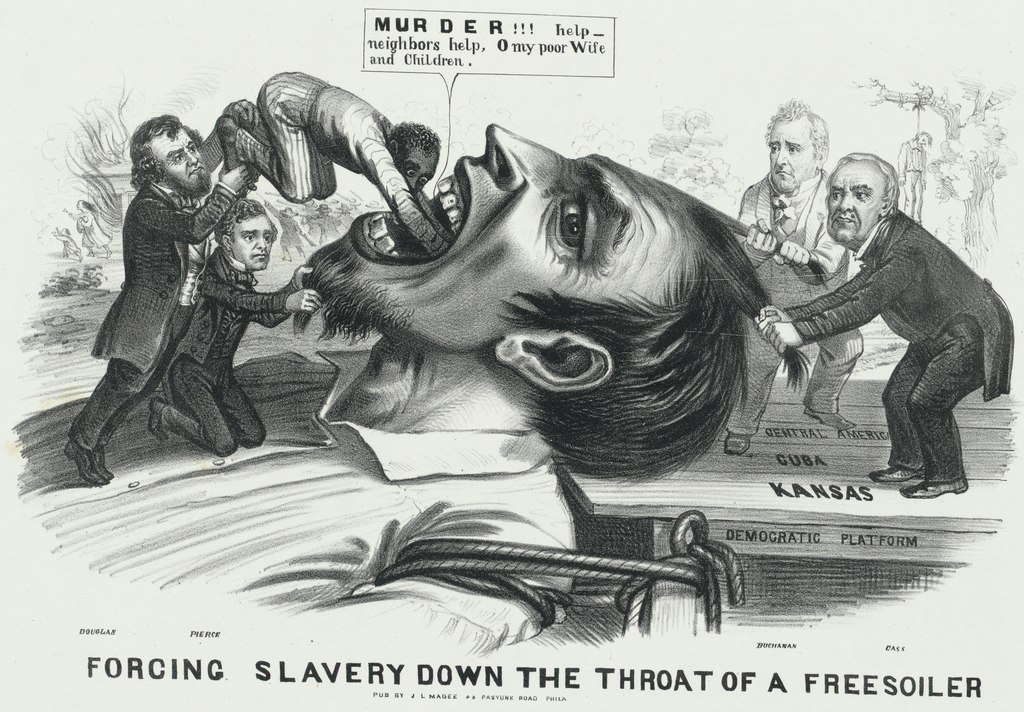

Taken at a thousand-foot glance, the fact that Kansas, a flat, barren waste smack in the middle of the so-called “Great American Desert” became the prelude to the greatest armed conflict in North America is so ridiculous it borders on farce. Before the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the land had been Indian Territory, the place the US government dumped its undesirables and tried to forget about them. White settlers who happened to be within the borders of what would become Kansas didn’t stay long as they headed west across the Sea of Grass in wagon trains along the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails. But by 1856, things were quickly going off the rails, because Stephen A. Douglas wanted to build a railroad.

Illinois Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas was the premiere apostle of

popular sovereignty, the idea that each new territory should vote on adopting or outlawing slavery prior to its entrance into the Union, throughout the decade. His main goal was the stabilization of the Union, embracing nationalism and the expansion of white settlement into the vast West as the bandage over the wound. That doctrine, he believed, was the way to make these dreams come true. He’d come close once before, drawing up a bill in 1854 that would repeal the Missouri Compromise and organize the Kansas Territory and the Nebraska Territory. He’d won the support of the president and many key Southron Democrats in the Senate, but unfortunately for Douglas and his dreams of a transcontinental railroad, a crisis had gotten in the way.

The Lane House

Lawrence, Kansas Territory

May 1, 1860

Lane and Brown found themselves in a dark room, the only light cast by the lone candle on the wooden table before them. Lining the walls were Lane’s most loyal Jayhawkers and Brown’s five sons, the flickering glow catching the whites of their eyes.

“The accession of this state under the Lecompton constitution is a blight upon this Union,” growled the prophet.

The commander nodded solemnly. “The president aims to bring slavery to this whole country, and I fear he may succeed, as he has in this state. The North remains fractured, but the South…”

“Have you heard that Buchanan has again refused to accept Oregon’s constitution?” called a Jayhawker.

Frederick Brown scoffed. “Have you heard that Senator Atchison has lent support to a bill that would bring popular sovereignty to

all Free States?”

A chorus of cries echoed through the room.

Lane sighed. “Unfortunately, at this stage, I believe more men in the North could stomach life under tyranny than life under liberty.”

“Do you believe the Republicans will win this election?”

The commander shook his head. “Not unless they make a stand. The Free Soilers have failed. A platform of anti-slavery expansion may as well be nothing at all.”

A particularly antsy Jayhawker piped up, “Then, what hope do we have?”

There was silence for a moment. Then, in a gravelly voice, John Brown declared, “Pharaoh has unleashed his fury onto us, and as Moses delivered the Israelites from Egypt, we too must deliver this land from slavery and tyranny. With whatever plagues God has granted us.”

The Election of 1860 was an affair almost as absurd as the fight for Kansas. President James Buchanan, a man reviled in the North, remained true to his campaign promise and did not run for reelection, leaving the Democratic National Convention an open playing field. The frontrunner was, of course, Stephen A. Douglas, but his nomination was hardly a sure thing. In 1858, during his run for reelection as Senator for Illinois, Douglas had to fight tooth-and-nail against former one-term US Representative Abraham Lincoln. Backed into a corner on the expansion of slavery, Douglas reaffirmed his support for popular sovereignty, thus opposing the declaration by the Supreme Court in

Dred Scott v. Sandford that slavery could not legally be excluded from US territories

at all. While this won him his seat in Illinois, where the

Dred Scott decision was hardly popular, it lost him the support of Southron Democrats.

Over the course of 44 ballots between April and May in Charleston, South Carolina, Douglas’ vote share slowly but surely began to diminish, especially as President Buchanan remained firmly supportive of Douglas’ key rival at the convention, sitting vice president John C. Breckinridge. But Douglas refused to concede. In a fit of exasperation toward the party’s cotton-crusted ruling class, the “Little Giant” took a great step forward. Vacating Charleston, he soon began touring the country, proclaiming his candidacy for president under the banner of a new party, the National Party, which embraced a platform of popular sovereignty in the territories, a transcontinental railroad, and greater expansion of American interests and borders. Hoping to stymie his impact, those who remained in Charleston added Daniel S. Dickinson, former Senator for New York, to the ballot as vice president, lending the Northern Democrats some prestige.

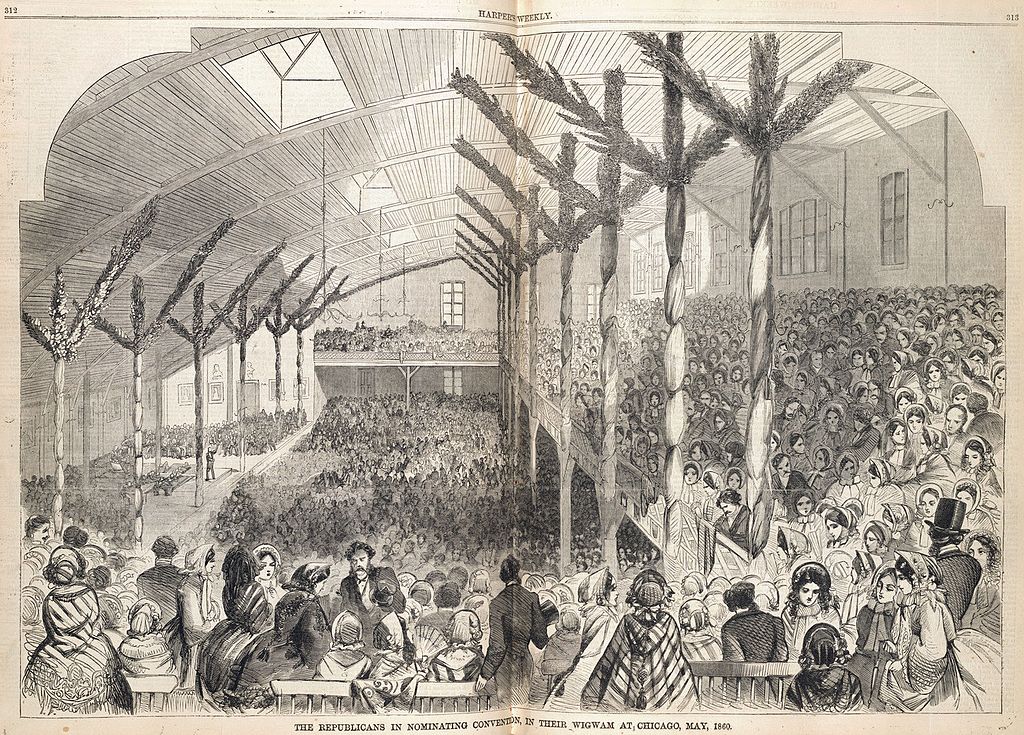

The newborn Republican Party was holding its own convention in Chicago. The party, a stitching-together of anti-slavery Whigs and Free Soilers, had stood controversial Mexican War veteran John C. Frémont on an anti-expansion platform and lost resoundingly. Hardly eager for a repeat of these results, and with the situation in America greatly deteriorated even compared to just four years prior, the 1860 convention was chaotic and divisive.

Senator William H. Seward of New York was at the head of the pack, but was hardly much more than a pace or two ahead of the others, which included Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, Governor Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, former representative Edward Bates of Missouri, and Senator Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, among others. Cassius Clay of Kentucky, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and Hannibal Hamlin of Maine all hovered at the periphery, their hats ready to be thrown into the ring should the opportunity arise.

As many predicted but few thought likely, Seward was chosen for the presidential ticket, with Clay stapled on as candidate for vice president. Despite his more radical nature spooking some of the moderate delegates, the overwhelming atmosphere in the Republican Party was that 1860 was the make-or-break moment for the Free Soil movement, and, to a lesser extent, abolitionism as a whole.

Seward was also, of course, greatly aided by the wonderful acoustics in the building the convention had been held in, the so-called “Wigwam” that had been purpose-built in Chicago just for the occasion, as the city (then of just 110,000 people) did not have a single place large enough to contain the event. His fiery “

Son of Liberty” speech condemned, among other things, the Democratic Party, slavery, the

Dred Scott decision, popular sovereignty, the Fugitive Slave Act, and the blockage of Oregonian statehood, and whipped the convention into a frenzy. The more moderate, “middle way” candidates were forgotten overnight. Though they remained reluctant to expressly write the abolition of slavery into the Republican platform, everyone from Maine to Florida knew that William H. Seward in the White House meant

change was coming.

“The debate between slavery and freedom is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slaveholding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation. Have we so soon forgotten the boons of liberty? Do we neglect the fact that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights? Across the bloody fields of Kansas, in the courtrooms of Illinois, on the very floor of the Senate itself, men fight for these rights! Our opponents, inextricably committed to the designs of the slaveholder class, wield the instruments of tyranny. They have forgotten that our nation is a son of Liberty.”

- William H. Seward, closing segment of the “Son of Liberty” speech

Republican National Convention, Chicago, Illinois

May 17, 1860

It was hardly a wonder, then, that William H. Seward lost to John C. Breckinridge.