Events in Italy are going to bring memories of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba to many... Alàs, for Enrique, Italy is just a secondary theatre of war.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

After the forest of Foixà: a new beginning for the House of Barcelona

- Thread starter Kurt_Steiner

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 85 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 78: The Second Great War: 1809-1810 (II) Chapter 79: After the War (1810-1820) Chapter 80: A Heated Post-War (1820-1830) Chapter 81: Hispania in the Post-War (1820-1830) Chapter 82: Hispania in the Post-War - II (1830-1831) Chapter 83: A Cultural Rennaisance Chapter 84. The Rising Sun and the Crescent Moon (1830-1842) Chapter 85: Brussels, 1843.

Chapter 15: The young king (1516-1520)

Chapter 15: The young king (1516-1520)

Eduardo I of Aragon and I of Castile was the first Aragonese king born outside of the Crown of Aragon. Born in Sevilla on January 28, 1499, he was the second son of Jaime V/I and was educated to become a mixture between a monk and a warrior, and he became fluent in Latin. Not much is known about his early life, because he was not expected to become king. It seems that the young Duke of Montblanch and of Toledo had a happy life until he was ten, when his elder brother Jaime died in 1509 and Eduardo became the heir of three kingdoms, a heavy weight for his unprepared shoulders. Then, Jaime V renewed his efforts to seal a marital alliance with England by offering his son Eduardo to marry Anne (1508-1554), the second daughter of Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger brother of Edward V, who was the uncle of Eduardo through his marriage with his aunt Margarita. This marriage was signed into a treaty on April 22, 1510 by Jaime's ambassador in England, Gutierre Álvarez de Toledo, who would become Bishop of Plasencia for his role in the signature of the treaty. The marriage would not take place until 1515, when Eduardo was 16 years old and Anne, 9.

The death of his heir had an unexpected problem to Jaime V. Antonio Manrique de Lara y Castro, 2nd Duke of Nájera and 3rd count of Treviño (1466-1519) was the great-grandson of Leonor de Castilla y Albuquerque, a bastard daughter of Fadrique de Castilla (1360-1394), who was also a bastard son, but of Enrique II of Castile. A proud and arrogant aristocrat, Jaime V feared that Manrique could become a suitable candidate for the crown. In addition to this, Manrique complained quite often that Jaime was not treating him with the respect he deserved. Shortly after the wedding treaty was signed, Manrique defected abroad and sought refuge in France. Jaime feared that he was not too loved in Castile and that many people would love to have one of their own as king. As Manrique, for instance. Declared a traitor, Manrique was deprived of all his titles and lands by act of the Castilian Cortes on January 19, 1512.

After his coronation, Eduardo issued a general pardon. Raised in Castile, he was the darling of the Castilian nobility and seen as the promise of a bright future with plenty of happiness, virtue and glory. In Aragon, the general attitude towards the new king was to wait and see, even if many voices whispered about the foreign, that is, Castilian, education that Enrique had received. Then, unexpectedly, four days after his coronation, Jaime arrested his father's two most unpopular ministers, Juan Manuel, lord de Belmonte and Juan Chacón de Alvarnáez, whose greed had made them perfect scapegoats for Eduardo, who directed on them the popular anger for the high taxes fixed by his father. However, while Belmonte and Chacón lost their heads to calm the commoners, the taxes remained in place.

During his first years as king, Eduardo became a very popular monarch. When the French Ambassador, Louis-Gui des Aimars, visited Eduardo's court, after meeting the king, he recorded that he was "extremely handsome; nature could not have done more for him." Eduardo was a passionate sportsman and seemed to be always filled with an endless source of energy, something that made him be jousting, sportung and hunting for hours without end. He loved to be outside and hated the long council meetings and the endless paper work. Eventually, he left that side of kingship Henry left to his right-hand man, Cardinal Alonso Manrique de Lara. He was also extremely passionate about tilting and jousting until a fatal accident in 1524, when he mortally wounded Luis de la Cueva y Toledo, the eldest son of Francisco Fernández de la Cueva y Mendoza, duke of Albuquerque.

The chronicles are filled with the new king. We are told that he was "the handsomest monarch I had ever put my eyes on", according to the Venetian ambassador; he was also above the usual height, and his complexion was "very fair and bright, with auburn hair combed straight and short, in the French fashion".

Whereas his father tended to dress in rather plain clothes, Eduardo I went for the extravagant. Clothes and jewels seemed like a good investment. Eduardo knew he was the King, and he was going to dress like one. His jacket was covered with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and pearls for his coronation. Over this wore a robe of crimson velvet trimmed with ermine. Finally, there was the piece de resistance, a huge collar of rubies from Afghanistan. Fond of jewellery, Eduardo kept many goldsmiths in a good income for many years. He tended to favour red, black, and gold in his outfits.

Thus, it seemed that a bright future for the king and his subjects was beginning to shine on the horizon.

Eduardo I of Aragon and I of Castile was the first Aragonese king born outside of the Crown of Aragon. Born in Sevilla on January 28, 1499, he was the second son of Jaime V/I and was educated to become a mixture between a monk and a warrior, and he became fluent in Latin. Not much is known about his early life, because he was not expected to become king. It seems that the young Duke of Montblanch and of Toledo had a happy life until he was ten, when his elder brother Jaime died in 1509 and Eduardo became the heir of three kingdoms, a heavy weight for his unprepared shoulders. Then, Jaime V renewed his efforts to seal a marital alliance with England by offering his son Eduardo to marry Anne (1508-1554), the second daughter of Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger brother of Edward V, who was the uncle of Eduardo through his marriage with his aunt Margarita. This marriage was signed into a treaty on April 22, 1510 by Jaime's ambassador in England, Gutierre Álvarez de Toledo, who would become Bishop of Plasencia for his role in the signature of the treaty. The marriage would not take place until 1515, when Eduardo was 16 years old and Anne, 9.

The death of his heir had an unexpected problem to Jaime V. Antonio Manrique de Lara y Castro, 2nd Duke of Nájera and 3rd count of Treviño (1466-1519) was the great-grandson of Leonor de Castilla y Albuquerque, a bastard daughter of Fadrique de Castilla (1360-1394), who was also a bastard son, but of Enrique II of Castile. A proud and arrogant aristocrat, Jaime V feared that Manrique could become a suitable candidate for the crown. In addition to this, Manrique complained quite often that Jaime was not treating him with the respect he deserved. Shortly after the wedding treaty was signed, Manrique defected abroad and sought refuge in France. Jaime feared that he was not too loved in Castile and that many people would love to have one of their own as king. As Manrique, for instance. Declared a traitor, Manrique was deprived of all his titles and lands by act of the Castilian Cortes on January 19, 1512.

After his coronation, Eduardo issued a general pardon. Raised in Castile, he was the darling of the Castilian nobility and seen as the promise of a bright future with plenty of happiness, virtue and glory. In Aragon, the general attitude towards the new king was to wait and see, even if many voices whispered about the foreign, that is, Castilian, education that Enrique had received. Then, unexpectedly, four days after his coronation, Jaime arrested his father's two most unpopular ministers, Juan Manuel, lord de Belmonte and Juan Chacón de Alvarnáez, whose greed had made them perfect scapegoats for Eduardo, who directed on them the popular anger for the high taxes fixed by his father. However, while Belmonte and Chacón lost their heads to calm the commoners, the taxes remained in place.

During his first years as king, Eduardo became a very popular monarch. When the French Ambassador, Louis-Gui des Aimars, visited Eduardo's court, after meeting the king, he recorded that he was "extremely handsome; nature could not have done more for him." Eduardo was a passionate sportsman and seemed to be always filled with an endless source of energy, something that made him be jousting, sportung and hunting for hours without end. He loved to be outside and hated the long council meetings and the endless paper work. Eventually, he left that side of kingship Henry left to his right-hand man, Cardinal Alonso Manrique de Lara. He was also extremely passionate about tilting and jousting until a fatal accident in 1524, when he mortally wounded Luis de la Cueva y Toledo, the eldest son of Francisco Fernández de la Cueva y Mendoza, duke of Albuquerque.

The chronicles are filled with the new king. We are told that he was "the handsomest monarch I had ever put my eyes on", according to the Venetian ambassador; he was also above the usual height, and his complexion was "very fair and bright, with auburn hair combed straight and short, in the French fashion".

Whereas his father tended to dress in rather plain clothes, Eduardo I went for the extravagant. Clothes and jewels seemed like a good investment. Eduardo knew he was the King, and he was going to dress like one. His jacket was covered with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and pearls for his coronation. Over this wore a robe of crimson velvet trimmed with ermine. Finally, there was the piece de resistance, a huge collar of rubies from Afghanistan. Fond of jewellery, Eduardo kept many goldsmiths in a good income for many years. He tended to favour red, black, and gold in his outfits.

Thus, it seemed that a bright future for the king and his subjects was beginning to shine on the horizon.

Last edited:

Got it! He's got much better stuff in store to be remembered by i'm sure!Don't rush... in the end, nobody is going to remember him for his fine looks...

Chapter 16: The perfect king (1520-1525)

Chapter 16: The perfect king (1520-1525)

By contrast with his father, Eduardo was a flamboyant king. He was a good monarch, sensible, reasonable and pleasant. with an endless sense of humour and he was always in a good mood. That was to have a great role in the events that were to unfold from 1521 onwards. Hernán Cortés had departed from San Damián (November 18, 1521) and followed a river that the natives called Paraná. Going up river, Cortés, who had 300 men with him, created several outposts (San Pedro, San Nicolás and Santa María -which later on would become a great city named Nuestra Señora del Rosario, o Rosario, for short). Pleased with Cortés. the governor of the province of San Damián, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, not only wrote to King Eduardo asking for more money and settlers, but also send more men and support to Cortés, who, in early May 1521, kept its upriver exploration (and also kept building outposts along the way) until he reached a point where the river broke into two. To the amazement of his captains, Cortés took the northward and smaller river. As Alonso Hernández Portocarrero wrote in one of his letters back to the Peninsula, Cortés looked as if "he was possessed by a strange fever". Actually, the exploration was cut short when Cortés became deeply ill, with a great part of his men. In spite of such a dissapointing end, Cortés was determined to try again later on.

Meanwhile, the island of Cuba had seen a change in the guard. The island, which had been discovered by accident by Caboto in his final voyage, would not attract any royal attention until 1522, as the first reports of Cortés' expedition arrived to the Peninsula. Eduardo I thought that the island could be a suitable base to explore the area. Thus, he sent Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), who had little time to organize the colony before dying and being replaced by Manuel de Rojas y Córdova (1494 – 1561). De Rojas thus supported the expedition of Alonso González Dávila (1485 – 1535), who, from June 1523 to April 1524, Dávila explored the Yucatan Peninsula and established a series of small outposts. However, when Dávila explored further inland, he met English explorers there, and, for a moment, it looked as if an diplomatic incident was on the verge of taking place. A frenzied traffic of letters and instructions flew from Cuba to Yucatan until a letter from Eduardo settled the issue in September 1524: Dávila was to withdraw to the Yucatan, while the English were to remain in control of the so-called "Mexica". This was the result of a personal agreement between Eduardo I and his English namesake, Edward V. Thus, Eduardo turned his attention to the south and, while Dávila remained organizing the Yucatan settlements and Cortés departed to explore again the Paraná. Diego de Ordás (1480-1542) thus departed from Cuba in the Spring of 1525 to explore the shores of the island of Trinidad, thus starting both the exploration and colonization of Venezuela . However, the lack of news about the discovery of El Dorado would push an impartiendo Eduardo I to overlook Venezuela, which only mattered to him as a springboard go discover the mysterious golden city. Thus, the process of colonization was trusted to De Ordás, while a new expedition under Francisco de Montejo (1479 - 1553) was being assembled in Cuba during the last months of 1525.

As we have seen, a possible conflict with England had been avoided through the direct intervention of Eduardo I. The 16th century is an unusual chapter in the long history of Spain's complex international relations. Eduardo I and Edward V enjoyed a mutual respect, even if sometimes was marked with deep suspicion about the real intentions of the other side. Eventually, this relation would change into an idiosyncratic compound of brotherhood, rivalry and mutual distrust. Under the treaty of London (October 4, 1518), they agreed as a gesture of good will to post one of their chamber gentlemen as ambassador resident at the other’s court. This was the first English resident embassy established by treaty and the only permanent English embassy of the century. The Spanish embassy in London ranked with those in Rome and Paris. The treaty was to led to the best-known royal meeting of the century, which took place at El Escorial, a magnificient palace built in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, one hundred kilómeters to the North of Toledo, in central Spain.

In addition to England, throughout the century there was also a diplomatic (and occasionally military) struggle for influence over Portugal, which also involved England due to the old ties that linked both countries. The reign of Eduardo would be thus characterised by a trilateral relationship between England, the Castilian-Aragonese Crown and Portugal. As it has been already mentioned, England began to emerge as a new power in Western Europe at that time, while the united Hispanic kingdoms were still a lessee power, and Eduardo, who wanted to have a saying in international politics, began to court hid English namesake.

He had already been successful in his talks with Francis I of France, They had signed the 1521 Treaty of Bordeaux, a non-aggression pact to help resist the Ottoman expansion into southeastern Europe, and that had also given Eduardo some international standing and fame. However, Edward I was not swayed by his Hispanic namesake as he considered that the English and Hispanic interests had too few elements in common and, thus, in spite of Eduardo's diplomatic moves.

However, as we shall see, this would radically change during the second half of th 1520s.

By contrast with his father, Eduardo was a flamboyant king. He was a good monarch, sensible, reasonable and pleasant. with an endless sense of humour and he was always in a good mood. That was to have a great role in the events that were to unfold from 1521 onwards. Hernán Cortés had departed from San Damián (November 18, 1521) and followed a river that the natives called Paraná. Going up river, Cortés, who had 300 men with him, created several outposts (San Pedro, San Nicolás and Santa María -which later on would become a great city named Nuestra Señora del Rosario, o Rosario, for short). Pleased with Cortés. the governor of the province of San Damián, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, not only wrote to King Eduardo asking for more money and settlers, but also send more men and support to Cortés, who, in early May 1521, kept its upriver exploration (and also kept building outposts along the way) until he reached a point where the river broke into two. To the amazement of his captains, Cortés took the northward and smaller river. As Alonso Hernández Portocarrero wrote in one of his letters back to the Peninsula, Cortés looked as if "he was possessed by a strange fever". Actually, the exploration was cut short when Cortés became deeply ill, with a great part of his men. In spite of such a dissapointing end, Cortés was determined to try again later on.

Meanwhile, the island of Cuba had seen a change in the guard. The island, which had been discovered by accident by Caboto in his final voyage, would not attract any royal attention until 1522, as the first reports of Cortés' expedition arrived to the Peninsula. Eduardo I thought that the island could be a suitable base to explore the area. Thus, he sent Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), who had little time to organize the colony before dying and being replaced by Manuel de Rojas y Córdova (1494 – 1561). De Rojas thus supported the expedition of Alonso González Dávila (1485 – 1535), who, from June 1523 to April 1524, Dávila explored the Yucatan Peninsula and established a series of small outposts. However, when Dávila explored further inland, he met English explorers there, and, for a moment, it looked as if an diplomatic incident was on the verge of taking place. A frenzied traffic of letters and instructions flew from Cuba to Yucatan until a letter from Eduardo settled the issue in September 1524: Dávila was to withdraw to the Yucatan, while the English were to remain in control of the so-called "Mexica". This was the result of a personal agreement between Eduardo I and his English namesake, Edward V. Thus, Eduardo turned his attention to the south and, while Dávila remained organizing the Yucatan settlements and Cortés departed to explore again the Paraná. Diego de Ordás (1480-1542) thus departed from Cuba in the Spring of 1525 to explore the shores of the island of Trinidad, thus starting both the exploration and colonization of Venezuela . However, the lack of news about the discovery of El Dorado would push an impartiendo Eduardo I to overlook Venezuela, which only mattered to him as a springboard go discover the mysterious golden city. Thus, the process of colonization was trusted to De Ordás, while a new expedition under Francisco de Montejo (1479 - 1553) was being assembled in Cuba during the last months of 1525.

As we have seen, a possible conflict with England had been avoided through the direct intervention of Eduardo I. The 16th century is an unusual chapter in the long history of Spain's complex international relations. Eduardo I and Edward V enjoyed a mutual respect, even if sometimes was marked with deep suspicion about the real intentions of the other side. Eventually, this relation would change into an idiosyncratic compound of brotherhood, rivalry and mutual distrust. Under the treaty of London (October 4, 1518), they agreed as a gesture of good will to post one of their chamber gentlemen as ambassador resident at the other’s court. This was the first English resident embassy established by treaty and the only permanent English embassy of the century. The Spanish embassy in London ranked with those in Rome and Paris. The treaty was to led to the best-known royal meeting of the century, which took place at El Escorial, a magnificient palace built in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, one hundred kilómeters to the North of Toledo, in central Spain.

In addition to England, throughout the century there was also a diplomatic (and occasionally military) struggle for influence over Portugal, which also involved England due to the old ties that linked both countries. The reign of Eduardo would be thus characterised by a trilateral relationship between England, the Castilian-Aragonese Crown and Portugal. As it has been already mentioned, England began to emerge as a new power in Western Europe at that time, while the united Hispanic kingdoms were still a lessee power, and Eduardo, who wanted to have a saying in international politics, began to court hid English namesake.

He had already been successful in his talks with Francis I of France, They had signed the 1521 Treaty of Bordeaux, a non-aggression pact to help resist the Ottoman expansion into southeastern Europe, and that had also given Eduardo some international standing and fame. However, Edward I was not swayed by his Hispanic namesake as he considered that the English and Hispanic interests had too few elements in common and, thus, in spite of Eduardo's diplomatic moves.

However, as we shall see, this would radically change during the second half of th 1520s.

Yes, Eduardo is doing fine, as the situation is quite normal. If (or when?) things begin to go downhill... then we shall see...Great to see that colonization is improving rapidly and that relations are good. Eduargo is doing pretty good so far.

Chapter 17: Clouds over Europe

Chapter 17: Clouds over Europe

Italy had become a mixed bag of success and failure for Francis I of France. What had started Francis tried and failed as Francis' bid to become Holy Roman Emperor at the Imperial election of 1519 ended in an open conflict after Francis failed in this Imperial enterprise, resulting in several campaigns with mixed results. The first one (1521–1526) broke when a French–Navarrese expedition attempted to reconquer Navarre after the Navarrese rebels offered the crown to Francis I. The reaction of Eduardo I sent the invaders back to France after crushing them at Baztan (August 20, 1521). This invasion could have been reduced to a Hispanic-French quarrel, when it grew out of proportion when Edward V of England used the chance to support his Hispanic namesake by securing an alliance with the Hispanic kingdom and then landing reinforcements at Calais. His next move, after offering an alliance to Burgundy, was to invade Brittany on behalf of Jacques of Brittany, who claimed to be the great-grandson of Arthur III, Duke of Brittany through his natural daughter named Jacqueline (who was legitimized in 1443). It was the beginning of a war that pitted France and the Republic of Venice against the Holy Roman Empire, England, the Hispanic kingdoms and the Papal States.

Sensing the delicate situation of Francis, the German Emperor, Karl V, invaded northeastern France (September 1520) but the stubborn resistance offered by Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard during the three-week siege of Mézières and the arrival of a great army under the command of the French king himself forced the withdrawal of the Imperial forces. Then, Francis turned his attention to the English. The fight began with French ships attacking English ones in the Channel and North Atlantic but, after a series of serious rebukes in the Channel, the French fleet centered its actions in the Atlantic, against the sealanes to the New World. This led a naval construction effort both in England and in the Hispanic kingdoms, as both kings greatly expanded their navies with larger Galleons (the Hispanic ones were to become the heaviest and heavily armed ships afloat in that time) to protect their own shipping and with light Caravels to harass the enemy fleets. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean Sea, Eduardo I had focused on the creation of a fleet of heavy galleys to counter the Ottoman expansion. The first attempt against Alger (1516) ended in failure, but Eduardo was to have better luck in 1518, when Hugo de Moncada, with 58 ships, annihilate the enemy fleet led by Khair ed-Din; then, the Hispanic land force, most of it Aragonese light infantry, landed in the city and sacked it in the most vicious way and then put it to torch. Alger would take almost a century to recover from the sacking. This would be followed, in 1525, by an Anglo-Hispanic expedition against Tunis, one of the main bases of Turkish piracy. This attack would be the first of many Anglo-Hispanic punitive expeditions (1537, 1541, 1555, 1572, 1593), which, in turn, became more of piracy raids against the base, as its sackings filled the royal treasuries while keeping the Turkish piracies at bay. Algiers would not recover until the early Dey period (1671-1682), but then fate repeated itself in 1682, when France bombarded Algiers for the first time, after which Admiral Duquesne also sacked Algiers.

Meanwhile, Karl V came into trouble in 1525 when the French recovered Milan and pushed the Imperial troops out of Italy. With Hispanic support, Karl V was able to trapp Francis I at Pavia, forcing his surrender after a two months siege. After Pavia, the fate of the French king, and of France itself, became the subject of furious diplomatic manoeuvring. Eduardo I, determined to take full profit of the situation, launched an invasion of Naples. The kingdom, in turmoil after the disaster of Pavia, suffered what Clausewitz named as "the first lightning war". The campaign, which lasted from October 9 to November 11, 1525, ended with the complete destruction of the Neapolitean armies and the conquest of the kingdom. To the scared eyes of the Pope and of Francis I, a new military power had appeared on the battlefield: the dreaded Tercios. Thus, Pope Clement VII became convinced that Kar'sl and Eduardo's growing power was a threat to his own position in Italy, and Venetian and papal envoys went to Francis suggesting an alliance against Charles.

Then, the world held its breath when it was know that the Aztecs had risen agains the European settlers and explorers (most of them English and a few Hispanic) and had annhilated them at the Battle of Ocotelolco (June 5, 1525) and then had massacred all the European settlements up to Cheapside (Veracruz OTL), which was finally taken and burnt to the ground in August of that year. Among the casualties there was Henry Tudor, Lord Hampton (1491 – 1525) and Lord Edward Grey (1487–1525) However, not all the European settlers were killed or sacrificied to the local goes, as a few of them were kept to extract information out or then. Be it through either threats or any kind of promises, a great part of the prisoners told the Mexica everything they knew either out of fear or gratitude for being spared. Thus, the Mexica began to adopt the Europeans' technology as much as they could. Firearms and cavalry were out of question as their lack of knowledge and familiarity to horses and arquebuses soon ended the investigations in this field. They were much more successful in adopting weapons such as pikes, swords, crossbows and even plate armor. Its production, however, was not only an artisan one, but also a very expensive process. For the moment, they had time to experiment and to expand, as Edward V had his hands full in Europe.

Italy had become a mixed bag of success and failure for Francis I of France. What had started Francis tried and failed as Francis' bid to become Holy Roman Emperor at the Imperial election of 1519 ended in an open conflict after Francis failed in this Imperial enterprise, resulting in several campaigns with mixed results. The first one (1521–1526) broke when a French–Navarrese expedition attempted to reconquer Navarre after the Navarrese rebels offered the crown to Francis I. The reaction of Eduardo I sent the invaders back to France after crushing them at Baztan (August 20, 1521). This invasion could have been reduced to a Hispanic-French quarrel, when it grew out of proportion when Edward V of England used the chance to support his Hispanic namesake by securing an alliance with the Hispanic kingdom and then landing reinforcements at Calais. His next move, after offering an alliance to Burgundy, was to invade Brittany on behalf of Jacques of Brittany, who claimed to be the great-grandson of Arthur III, Duke of Brittany through his natural daughter named Jacqueline (who was legitimized in 1443). It was the beginning of a war that pitted France and the Republic of Venice against the Holy Roman Empire, England, the Hispanic kingdoms and the Papal States.

Sensing the delicate situation of Francis, the German Emperor, Karl V, invaded northeastern France (September 1520) but the stubborn resistance offered by Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard during the three-week siege of Mézières and the arrival of a great army under the command of the French king himself forced the withdrawal of the Imperial forces. Then, Francis turned his attention to the English. The fight began with French ships attacking English ones in the Channel and North Atlantic but, after a series of serious rebukes in the Channel, the French fleet centered its actions in the Atlantic, against the sealanes to the New World. This led a naval construction effort both in England and in the Hispanic kingdoms, as both kings greatly expanded their navies with larger Galleons (the Hispanic ones were to become the heaviest and heavily armed ships afloat in that time) to protect their own shipping and with light Caravels to harass the enemy fleets. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean Sea, Eduardo I had focused on the creation of a fleet of heavy galleys to counter the Ottoman expansion. The first attempt against Alger (1516) ended in failure, but Eduardo was to have better luck in 1518, when Hugo de Moncada, with 58 ships, annihilate the enemy fleet led by Khair ed-Din; then, the Hispanic land force, most of it Aragonese light infantry, landed in the city and sacked it in the most vicious way and then put it to torch. Alger would take almost a century to recover from the sacking. This would be followed, in 1525, by an Anglo-Hispanic expedition against Tunis, one of the main bases of Turkish piracy. This attack would be the first of many Anglo-Hispanic punitive expeditions (1537, 1541, 1555, 1572, 1593), which, in turn, became more of piracy raids against the base, as its sackings filled the royal treasuries while keeping the Turkish piracies at bay. Algiers would not recover until the early Dey period (1671-1682), but then fate repeated itself in 1682, when France bombarded Algiers for the first time, after which Admiral Duquesne also sacked Algiers.

Meanwhile, Karl V came into trouble in 1525 when the French recovered Milan and pushed the Imperial troops out of Italy. With Hispanic support, Karl V was able to trapp Francis I at Pavia, forcing his surrender after a two months siege. After Pavia, the fate of the French king, and of France itself, became the subject of furious diplomatic manoeuvring. Eduardo I, determined to take full profit of the situation, launched an invasion of Naples. The kingdom, in turmoil after the disaster of Pavia, suffered what Clausewitz named as "the first lightning war". The campaign, which lasted from October 9 to November 11, 1525, ended with the complete destruction of the Neapolitean armies and the conquest of the kingdom. To the scared eyes of the Pope and of Francis I, a new military power had appeared on the battlefield: the dreaded Tercios. Thus, Pope Clement VII became convinced that Kar'sl and Eduardo's growing power was a threat to his own position in Italy, and Venetian and papal envoys went to Francis suggesting an alliance against Charles.

Then, the world held its breath when it was know that the Aztecs had risen agains the European settlers and explorers (most of them English and a few Hispanic) and had annhilated them at the Battle of Ocotelolco (June 5, 1525) and then had massacred all the European settlements up to Cheapside (Veracruz OTL), which was finally taken and burnt to the ground in August of that year. Among the casualties there was Henry Tudor, Lord Hampton (1491 – 1525) and Lord Edward Grey (1487–1525) However, not all the European settlers were killed or sacrificied to the local goes, as a few of them were kept to extract information out or then. Be it through either threats or any kind of promises, a great part of the prisoners told the Mexica everything they knew either out of fear or gratitude for being spared. Thus, the Mexica began to adopt the Europeans' technology as much as they could. Firearms and cavalry were out of question as their lack of knowledge and familiarity to horses and arquebuses soon ended the investigations in this field. They were much more successful in adopting weapons such as pikes, swords, crossbows and even plate armor. Its production, however, was not only an artisan one, but also a very expensive process. For the moment, they had time to experiment and to expand, as Edward V had his hands full in Europe.

Trashing France is a good use that should be maintained at all costs. The Naples thing, I must confess, was a way to mess everything a bit more...Very happy to see Francis and France getting their asses handed to them and that Eduardo managed to reclaim naples for Spain.

Bad incident in the colonization front aside, things seem to be doing good for Eduardo.

Well, from time to time is a good thing to have the American natives having the upper hand, don't you think?

Trashing France always brings a smile to my face and Naples will increase spanish influence.Trashing France is a good use that should be maintained at all costs. The Naples thing, I must confess, was a way to mess everything a bit more...

Well, from time to time is a good thing to have the American natives having the upper hand, don't you think?

And agreed.

And Hispanic troubles with the Pope.Trashing France always brings a smile to my face and Naples will increase spanish influence.

And agreed.

No kidding.And Hispanic troubles with the Pope.

Excellent chapter. Now without Europeans I see the different tribes will go to war for power and what they learn from the survivors, besides being costly will be limited for a while.

Well, without the Europeans (for a while) and with the Aztecs determined to prove their might and to test their new weapons the fight may be quite interesting to see.Excellent chapter. Now without Europeans I see the different tribes will go to war for power and what they learn from the survivors, besides being costly will be limited for a while.

Chapter 18: Clouds over Barcelona (1516-1525)

Chapter 18: Clouds over Barcelona (1516-1525)

As the war was going on in Italy, Hernan Cortés finally had his chance to prove his might. After exploring the Paraná river, tired of his demands for more men to explore further west, the governor of La Plata₁ , Juan Pedro Díaz de Solís, managed to send him back to the Peninsula in the summer of 1525. When he finally arrived to the Peninsula, he found himself shipped with the Tercios that were to reinforce the Hispanic holding of Naples. For a while, Cortés was going to be away of America and thus it fell on Diego de Ordás, who had managed to explore the shores of present day Venezuela and establish a few outposts. However, as Bartolomé de las Casas would write to the king, "de Ordás seemed to be possesd by the Devil, as he was completely obssesed to exploring further west"; however, de Ordás was luckier than Cortés and for his efforts he was given the command of six ships. It was the beginning of what, eventually, would be the Hispanic conquest of the Inca Empire.

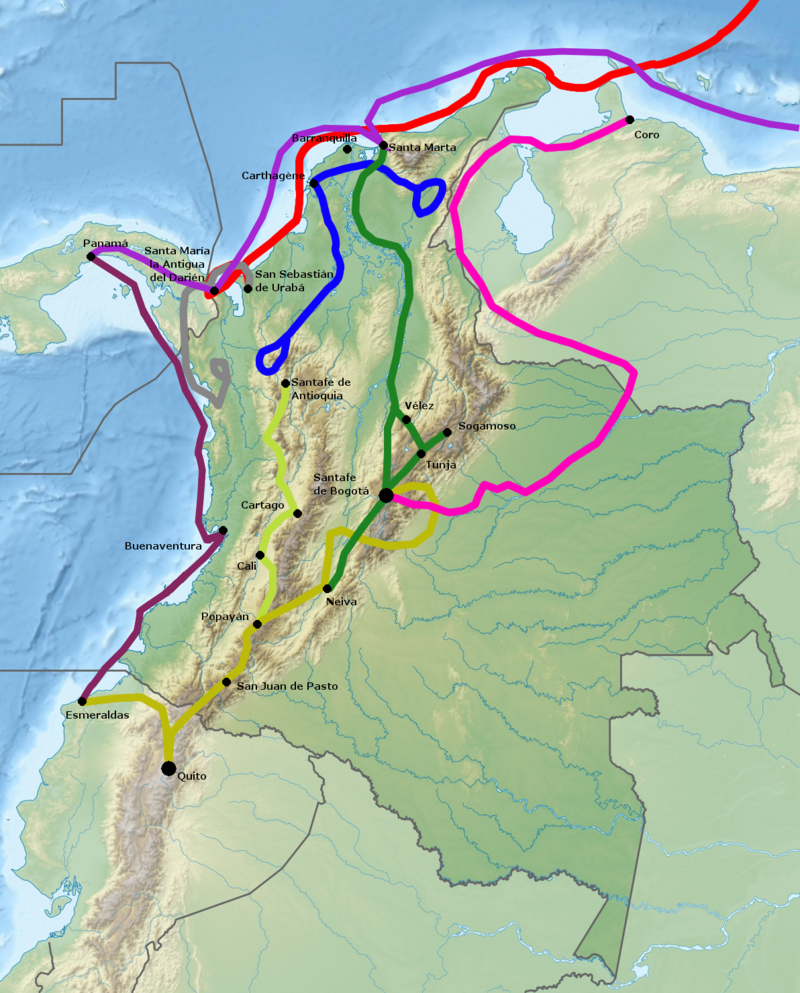

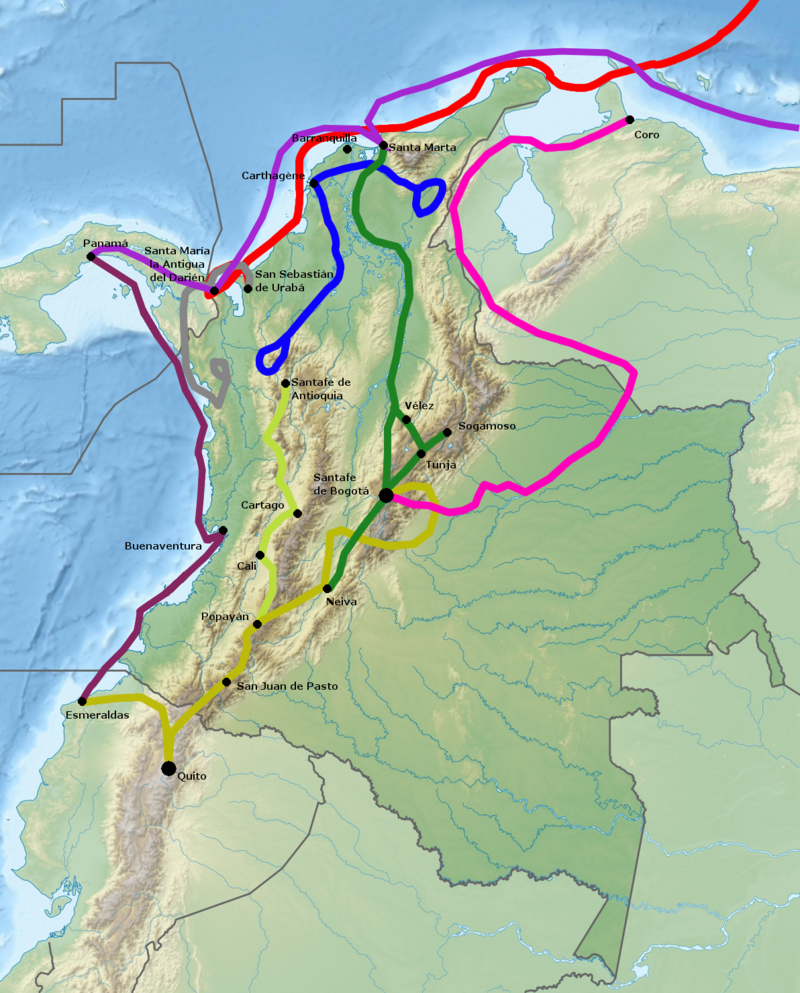

Red: Diego de Ordás (1525-1526); grey: Alonso de Ojeda (1528); lilac: Diego de Almagro (1529-1531); purple: Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1529-1531);

blue: Pedro de Candía (1530-1536); yellow: Francisco Pizarro (1533-1545); green: Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (1541-1544); pink: Nicolás Federmann (1542-1544)

While Diego de Ordás, Diego de Almagro and Alonso de Ojeda (1525-1531) explored the north and west coast of America, discovering the so-called "Mar del Sur", that is, the Pacific Ocean, as they were looking for the "Birú", that is, the Inca Empire, which was thorn by a vicious civil war. Thus, when Vasco Núñez de Balboa arrived to what was to become San Mateo de las Esmeraldas, he found a decaying and weak empire that was hardly able to defend itself. Balboa had with him barely 200 mem with him, but they were widely equipped with arquebuses and after a few skirmishes, their firepower deeply impressed one of the Inca pretenders, Huascar, who offered Balboa endless riches to help him in his war against Atahualpa, and dooming the Inca Empire without being aware of it. After a few battles, Atahualpa's forces were terribly mauled and his own men turned against him. Atahualpa was murdered in early 1544. Huascar seemed on the verge of victory, when Balboa turned against him. In the summer of 1545, Balboa, after joining hands with Pizarro, arrested and executed Huascar. However, this left him in control of barely the north of the Inca Empire, which by then it was broken itself into several small kingdoms that kept fighting among them.

However, Balboa's legend was to be somewhat obscured by the European events.

The chronicles claim that the sun began to set upon Eduardo I's realms after the death of his elder son, also called Jaime, in 1523. Jaime was 33 and died in a hunting accident, who was survived by two daughters; Violante and Constanza, so the king wasted no time to declare his second son Eduardo as Prince of Asturias and Duke of Girona. Eduardo, by then, had one son, Alfonso (b. in 1508), who became the future of the house of Barcelona. It is time, also, to take a look on the Hispanic Royal Family. In addition to Eduardo I's son, there were his cousins:

-Pedro, Duke of Palma (1462-1494), and his son and heir, Juan (1481-1514), his son Alfonso (1465-1525) and his daughter María (1470-1560).

-Tomas, Duke of Alcubierre (1440-1505) had two sons, Alfonso (1466-1513) and Enrique (1472-1514 )

-Ramon Berenguer, Duke of Lucena (1441-1502), had two sons, Berenguer (1452-1505), and one daughter, María (b. in 1454-1540), who was married to Pedro III of Urgell (1440-1466), with whom she had a son, Jaime, and two daughters.

The chronicles explain that Juan, the future Duke of Palma, had a tense relations with his cousins Alfonso, the future Duke of Alcubierre, and Enrique, the future Duke of Trastámara, that only went worse with time, until it became a deep hatred when they became grown men. As we shall see, this hatred was to cause a terrible drama.

₁ - PD Argentina

As the war was going on in Italy, Hernan Cortés finally had his chance to prove his might. After exploring the Paraná river, tired of his demands for more men to explore further west, the governor of La Plata₁ , Juan Pedro Díaz de Solís, managed to send him back to the Peninsula in the summer of 1525. When he finally arrived to the Peninsula, he found himself shipped with the Tercios that were to reinforce the Hispanic holding of Naples. For a while, Cortés was going to be away of America and thus it fell on Diego de Ordás, who had managed to explore the shores of present day Venezuela and establish a few outposts. However, as Bartolomé de las Casas would write to the king, "de Ordás seemed to be possesd by the Devil, as he was completely obssesed to exploring further west"; however, de Ordás was luckier than Cortés and for his efforts he was given the command of six ships. It was the beginning of what, eventually, would be the Hispanic conquest of the Inca Empire.

Red: Diego de Ordás (1525-1526); grey: Alonso de Ojeda (1528); lilac: Diego de Almagro (1529-1531); purple: Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1529-1531);

blue: Pedro de Candía (1530-1536); yellow: Francisco Pizarro (1533-1545); green: Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (1541-1544); pink: Nicolás Federmann (1542-1544)

However, Balboa's legend was to be somewhat obscured by the European events.

The chronicles claim that the sun began to set upon Eduardo I's realms after the death of his elder son, also called Jaime, in 1523. Jaime was 33 and died in a hunting accident, who was survived by two daughters; Violante and Constanza, so the king wasted no time to declare his second son Eduardo as Prince of Asturias and Duke of Girona. Eduardo, by then, had one son, Alfonso (b. in 1508), who became the future of the house of Barcelona. It is time, also, to take a look on the Hispanic Royal Family. In addition to Eduardo I's son, there were his cousins:

-Pedro, Duke of Palma (1462-1494), and his son and heir, Juan (1481-1514), his son Alfonso (1465-1525) and his daughter María (1470-1560).

-Tomas, Duke of Alcubierre (1440-1505) had two sons, Alfonso (1466-1513) and Enrique (1472-1514 )

-Ramon Berenguer, Duke of Lucena (1441-1502), had two sons, Berenguer (1452-1505), and one daughter, María (b. in 1454-1540), who was married to Pedro III of Urgell (1440-1466), with whom she had a son, Jaime, and two daughters.

The chronicles explain that Juan, the future Duke of Palma, had a tense relations with his cousins Alfonso, the future Duke of Alcubierre, and Enrique, the future Duke of Trastámara, that only went worse with time, until it became a deep hatred when they became grown men. As we shall see, this hatred was to cause a terrible drama.

₁ - PD Argentina

Last edited:

No, your senses fail you here.Great to see colonization progress.

And crap! Sensing another civil war on the horizon!

Threadmarks

View all 85 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 78: The Second Great War: 1809-1810 (II) Chapter 79: After the War (1810-1820) Chapter 80: A Heated Post-War (1820-1830) Chapter 81: Hispania in the Post-War (1820-1830) Chapter 82: Hispania in the Post-War - II (1830-1831) Chapter 83: A Cultural Rennaisance Chapter 84. The Rising Sun and the Crescent Moon (1830-1842) Chapter 85: Brussels, 1843.

Share: